A year ago, the US economy tanked. Will it return to normal once the pandemic is over?

image copyrightReuters

What a difference a year makes. When the pandemic began, the BBC spoke to some economists to make sense of what was happening to the US economy. We went back to those same experts to see how things played out, and what they’re keeping their eye on in the future.

At the time, they all said they thought the country would fare better than it did the last time it was faced with widespread economic uncertainty, during the 2008 economic recession.

But they also had some worries, about how much the government would intervene and how effective the country’s vaccine programme would be.

When the pandemic hit the US hard in the spring of 2020, everything ground to a halt.

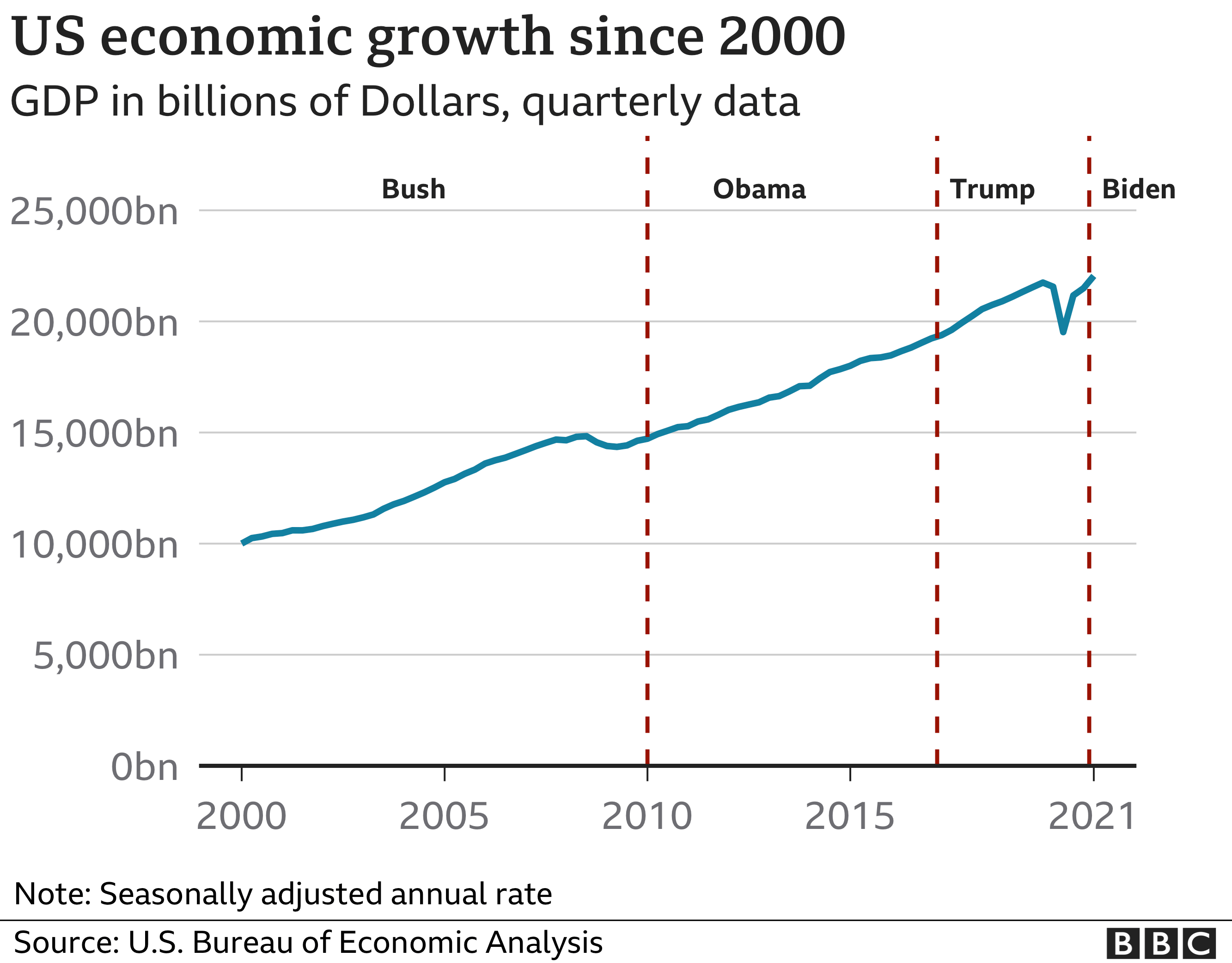

In a single month, 17 million Americans lost their job, and the gross domestic product (GDP), which is how economists measure the total value of a country’s products and services, declined by $2.15tn (£1.55tn).

The country hadn’t seen a dip like that since the 2008 financial collapse.

image copyrightBBC News

And like during the financial crisis, the US government needed to act quickly to avoid further damage, says Todd Knoop, an economist who researches the history of recessions at Cornell College.

When the BBC spoke with Mr Knoop last June, he was hopeful government spending and monetary policy would keep the economy from totally collapsing.

So what actually happened?

Mr Knoop’s prediction was right on the money. Congress passed a series of aid packages worth trillions of dollars. He believes these supports, which included direct payments to Americans and extended unemployment benefits, helped keep many people afloat even when they were out of work.

“In almost every factor, things have turned out better than worst-case scenario, and that’s great,” says Mr Knoop now.

The GDP has rebounded, 6.4% in the first three months of the year.

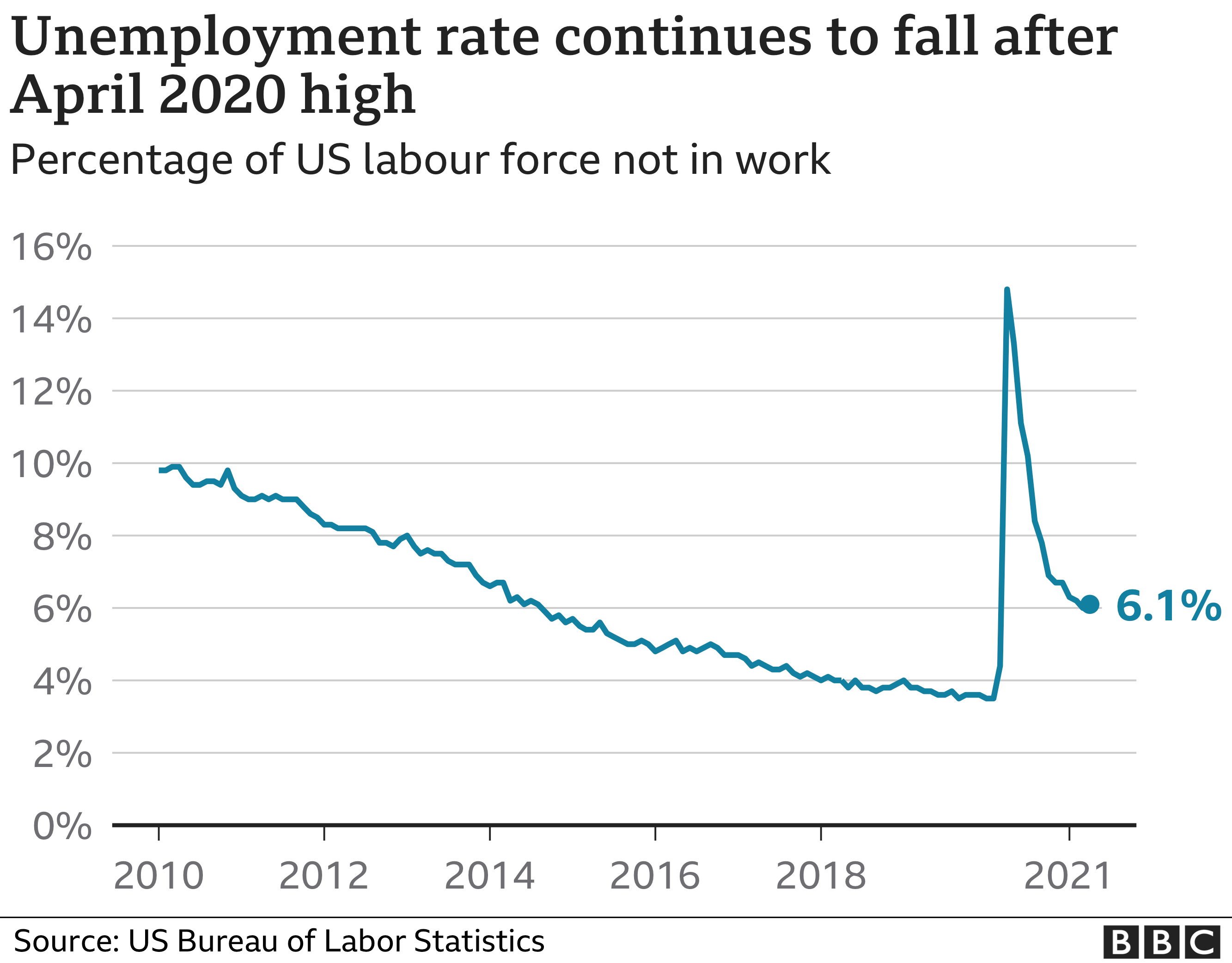

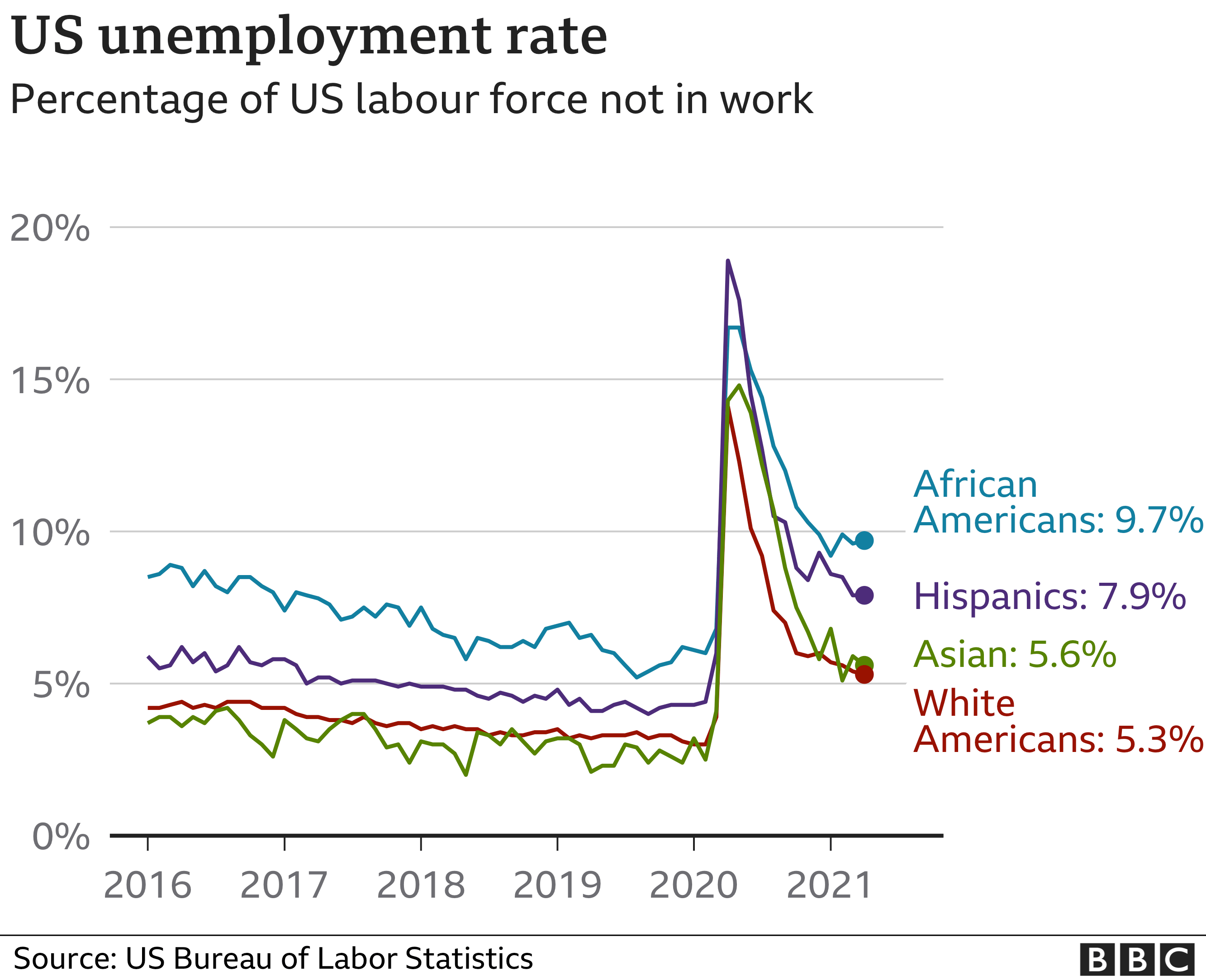

While the unemployment rate is still higher than it was pre-pandemic, about 15 million Americans went back to work, which is also good news.

image copyrightBBC News

Campbell Harvey, an economist at Duke University, agrees.

Last June, he likened the pandemic to a hurricane, which wipes out businesses and homes indiscriminately. Pandemic spending is akin to disaster relief, he argued.

But even with government aid, many small businesses have gone under or are struggling, he says, and that will leave a mark on the economy as a whole.

“They don’t make the headlines – you’ve never heard of them, they might be like a two-person operation, but that’s some damage,” he says.

During the first wave of lockdowns and stay-at-home orders last spring, Mr Knoop says it was clear that industries that relied on in-person customers – like travel and some retail – were going to struggle, while others would more easily adapt to the “new normal”.

“This is really destroying people and it’s destroying human systems, in the way we share ideas and technology and interacting with each other,” he said at the time.

What actually happened:

Mr Knoop was right – the pandemic decimated some industries and boosted others.

Tech-heavy companies that delivered products or services to people’s homes – like Amazon, Netflix, and Shopify —thrived.

Amazon tripled its profits during the pandemic, making founder Jeff Bezos’s personal wealth grow to $202bn according to Bloomberg’s Billionaire Index.

image copyrightBBC News

Meanwhile, entire industries like hospitality and transportation saw widespread collapse, with millions still out of work.

The National Restaurant Association says their industry lost $115bn in sales when comparing 2020 sales to 2019, while the aviation industry has received about $55bn in bailout money from the federal government.

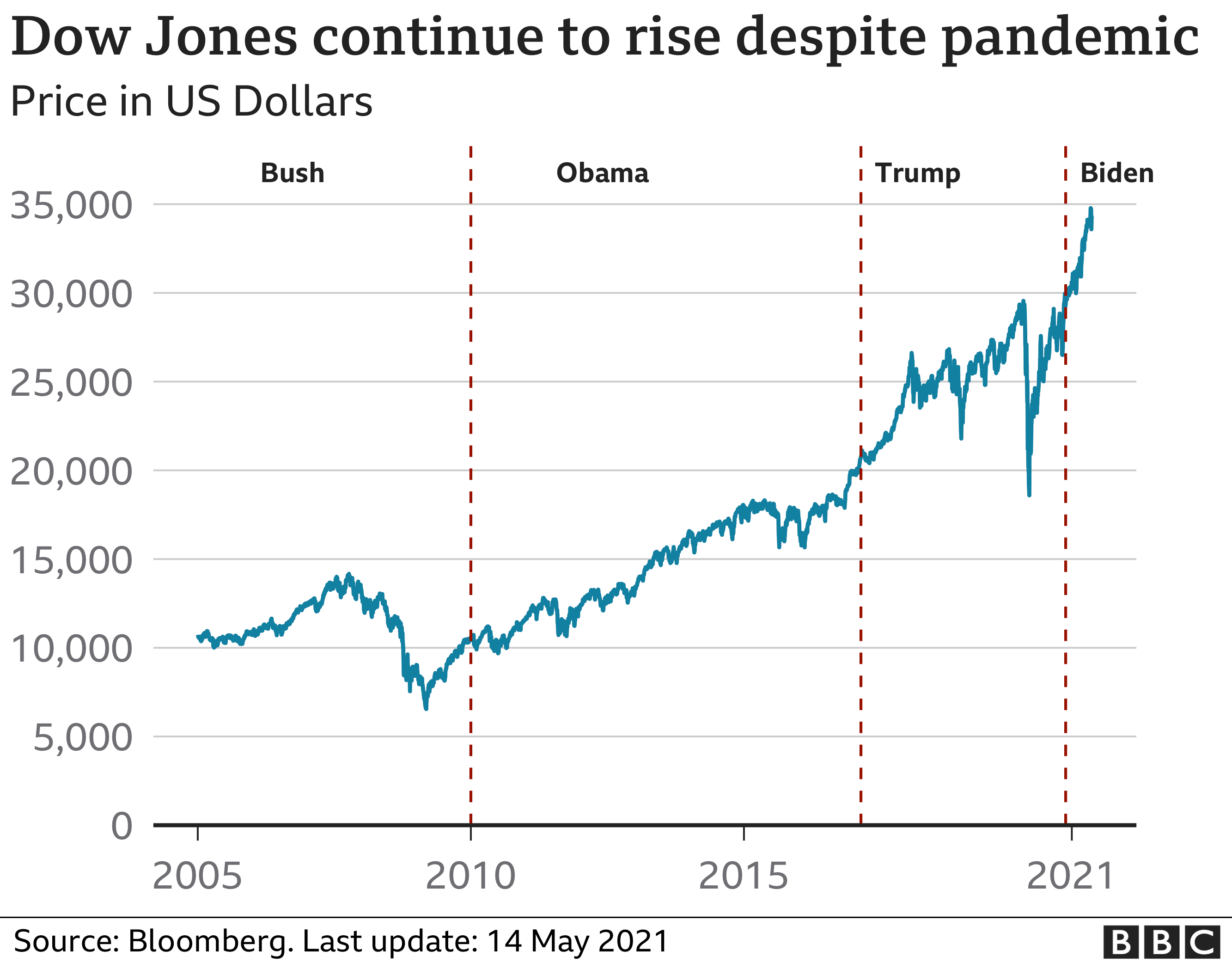

When the Dow Jones dropped nearly 3,000 points in a single day on 16 March 2020, many panicked.

But Mr Harvey predicted that as soon as viable vaccines emerged, the economy would rebound.

“There is light at the end of the tunnel, and that light was being driven by a vaccine,” he says.

What actually happened:

Wall Street did rebound – and then some.

The stock market has gone on to reach record highs since that record low on that March day, with the Dow Jones almost doubling in a year, reaching an all-time high of 34,200.67 points on 16 April, when almost 40% of Americans had received at least one dose.

While this boom is even bigger than Mr Harvey expected, he remains cautious about what this means for long-term economic recovery.

“Essentially the stock market has come to the view that the pandemic didn’t happen. It’s like oh, we’re just back to exactly where we were. That is hard to buy,” he says.

Mr Harvey says market’s dizzying rebound, combined with low interest rates, has led many people to make decisions with “rose-coloured glasses”, from buying their dream home in the country to taking out a big loan on their business – and that could lead to more economic trouble down the road if the economy hits rocky waters again.

image copyrightBBC News

Something that could trigger another recession would be if new variants prove resistant to vaccines, or if there was a problem in vaccine delivery.

Mr Harvey is critical of how Western nations have hoarded vaccines, noting that the longer other countries wait for vaccines, the longer the virus has to mutate.

“There really is no border when it comes to a pandemic,” he says.

“It’s global, and the longer you wait in terms of vaccination, the higher probability you have of these variants that are much more contagious and much more deadly.”

While both Mr Harvey and Mr Knoop think the economy has made a strong recovery this past year, they also have concerns about the future.

“Some of these risks are bigger today than they were a year ago, and that leads me to be cautious about the path forward,” Mr Harvey says.

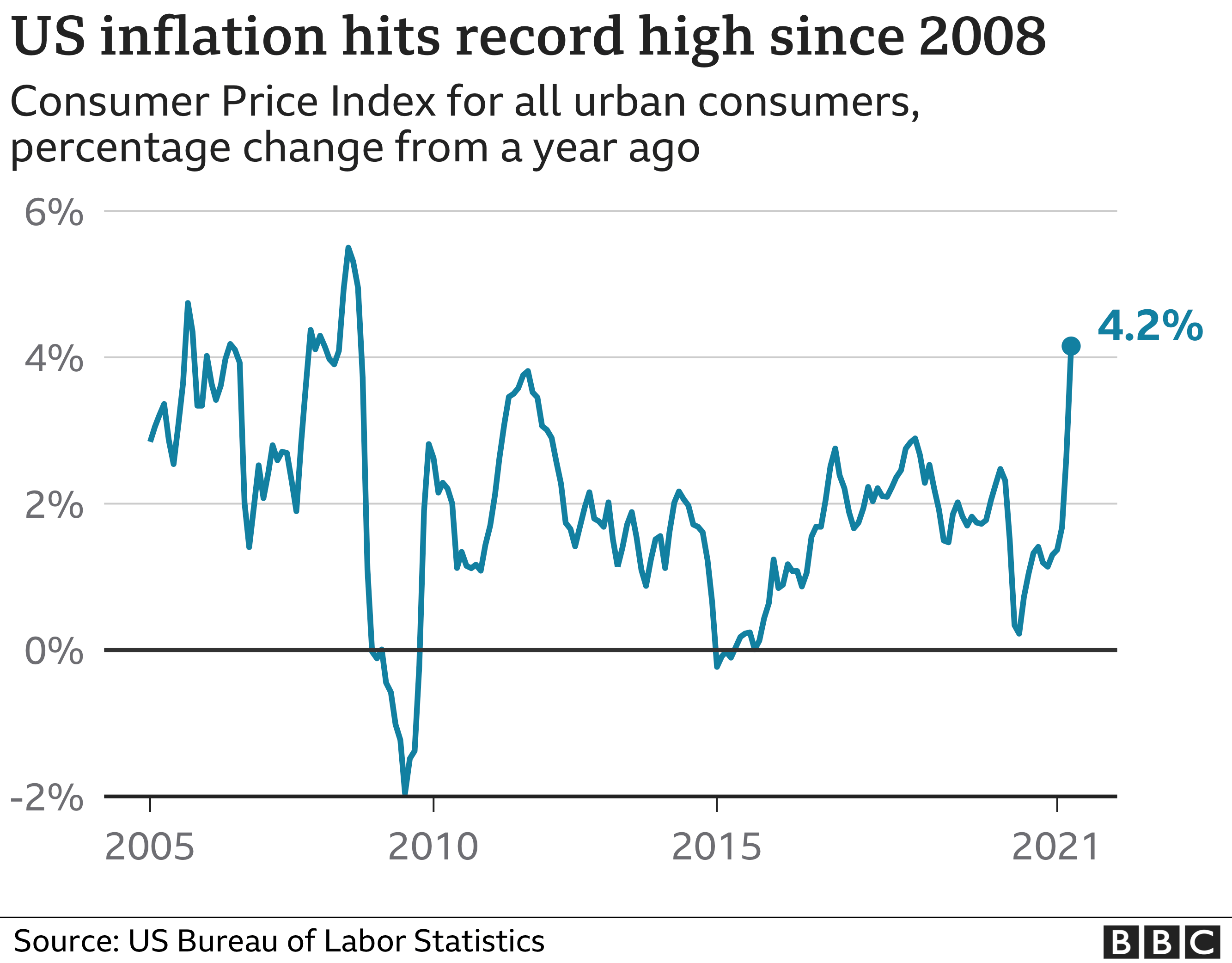

One of Mr Harvey’s biggest concerns is the risk of unexpected inflation, not necessarily in the short term, but in the years to come.

image copyrightBBC News

When governments borrow money to inject the economy with additional spending, as they have done, it can trigger a rise in both interest rates and the prices of ordinary goods.

“People believe you can just spend and there is no consequence – there is a consequence, we’re just expropriating from our children and grandchildren,” he warns.

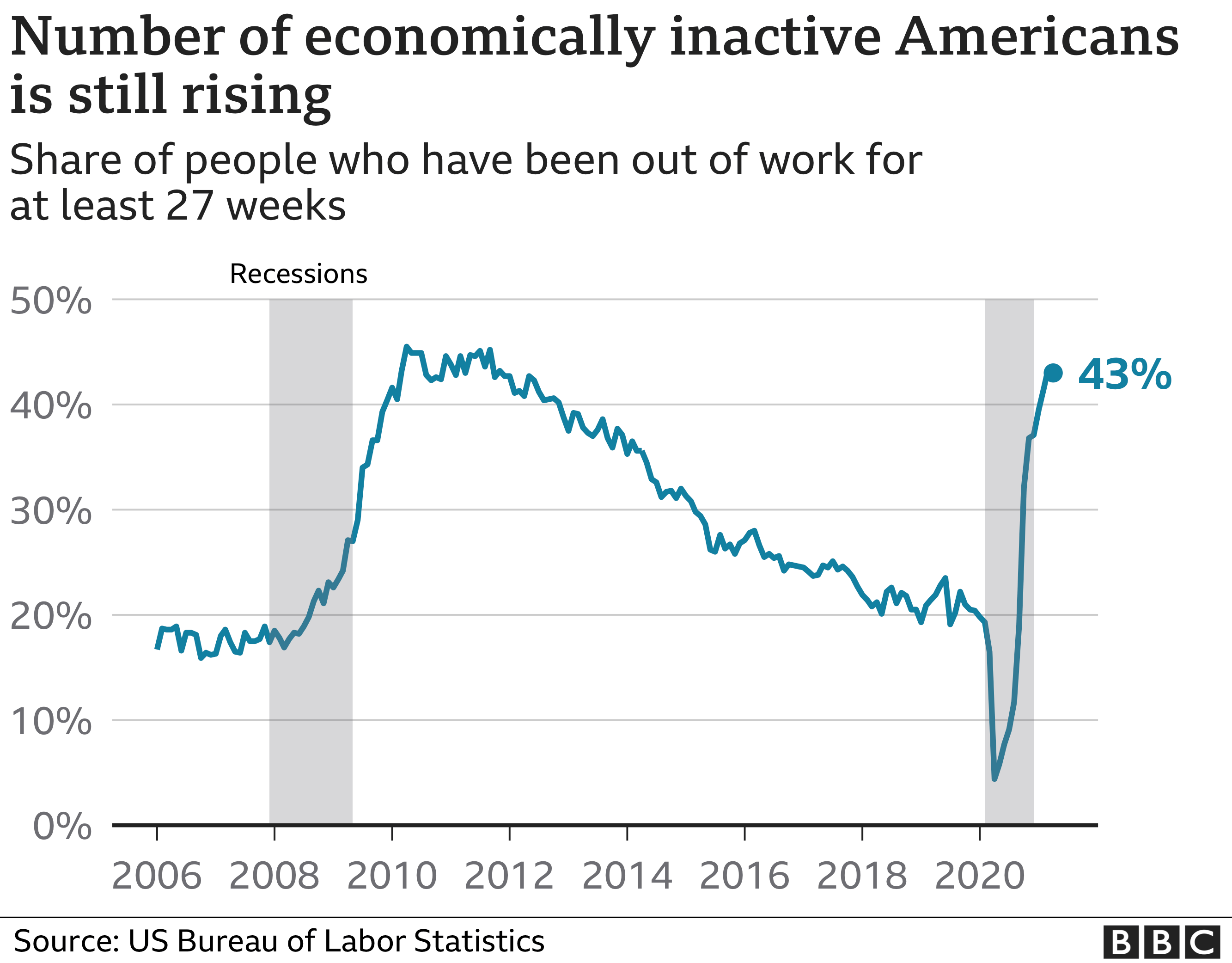

For Mr Knoop, his long-term concern is about how uneven the country’s economic recovery has been. Some people have thrived, while others have struggled, often along long-established fault lines of inequality such as race and gender, he says.

“A year ago I would have anticipated inequality getting worse but the part of inequality I maybe wouldn’t have appreciated is how well people at the top have done during Covid,” he says.

“I never would have expected the stock market to go so high, the real-estate boom to go up – people that had wealth before Covid have actually done very, very well.”

image copyrightBBC News

Meanwhile, many lower-paid workers in the service industry have seen their jobs disappear or their hours cut back, or if they are essential workers, they’ve had to put their health and safety on the line to go to work.

This widening inequality is bad news for the economy, Mr Knoop says, because it negatively effects so many aspects of our society, such as health, wealth, education and crime.

“Inequality is bad for economic growth – it’s bad for economic growth today, it’s bad for educational outcomes which means worse economic growth in the future,” he says.