Rule Britannia has had its place – but so have Bovril, balls, Blackshirts and a bombastic celebration of the Bard.

image copyrightGetty Images

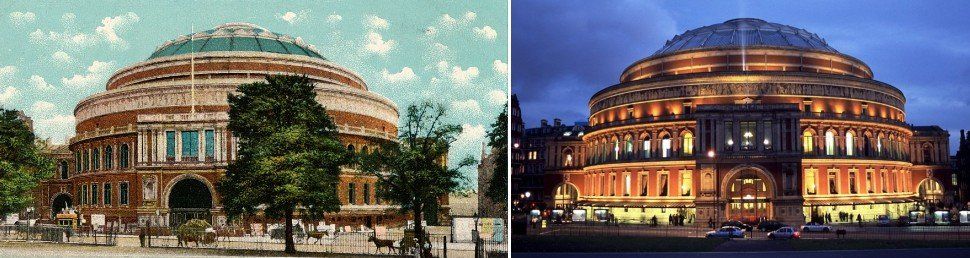

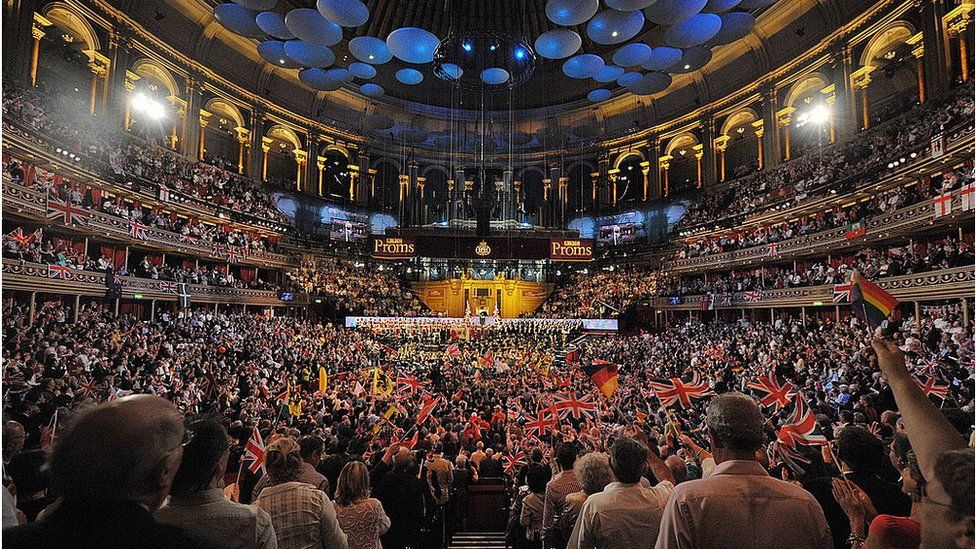

Perhaps best known for classical music and the Last Night of the Proms, the Royal Albert Hall has a far from stuffy past. Rule Britannia has had its place – but so have Bovril, balls, Blackshirts and a bombastic celebration of the Bard.

On the 150th anniversary of its opening, its archive manager Liz Harper insists “the idea of it being an elitist venue is just not true,” describing it as the “nation’s village hall” because of its eclectic events and occupants.

So, from the flushed faces of middle England bobbing beneath their Union Jacks to the flushed lavatories reinforced for Sumo competitors, here are some of the Royal Albert Hall’s highs and lows over the past century and a half.

image copyrightGetty Images

Prince Albert, along with Henry Cole – a civil servant with a passion for art and industrial design – organised 1851’s hugely popular Great Exhibition; a world fair which was held in Hyde Park.

The profits of that were used to buy land and develop institutions in South Kensington, including the Natural History Museum, the V&A, and Imperial College.

The centrepiece of this area of academia and aestheticism was a giant hall, the manifestation of Prince Albert’s idea of a hub where people could gather and share ideas. At the opening ceremony on 29 March 1871, Queen Victoria was overcome by emotion (she was not amused), and her son the Prince of Wales had to speak on her behalf.

Money was raised for construction by selling tickets in advance. The first 20 were bought by Queen Victoria. They still make up the royal box.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightBrigham Young University

The building was designed by engineers rather than architects, with the emphasis placed firmly on functionality. Taking almost four years to build, it cost the equivalent of more than £20m today.

“Even when it first opened, people said it wasn’t the most beautiful,” explains Ms Harper.

“But as a functional public building I think it’s stood the test of time.”

It was far from plain sailing. During the first few years, the hall hosted various events with mixed success.

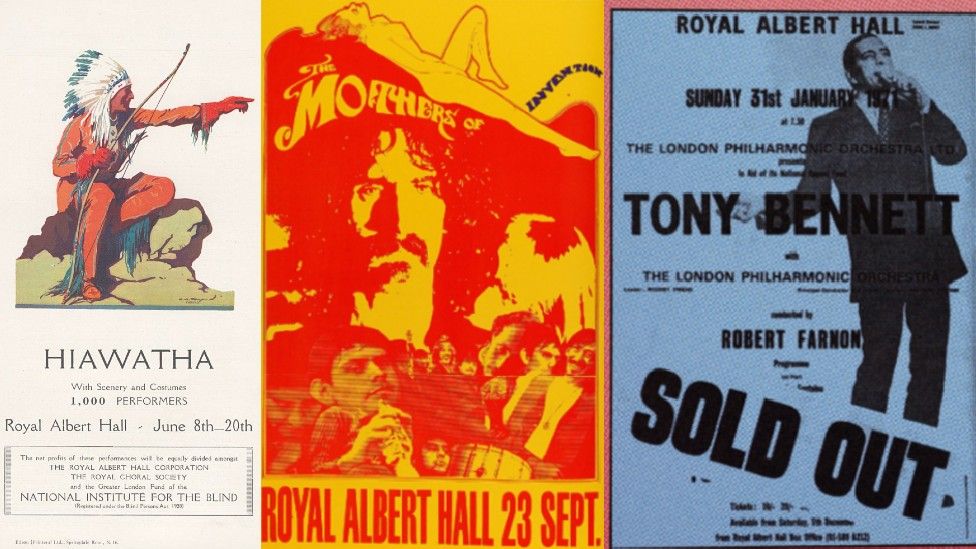

Ms Harper says popular shows included huge thousand-person choirs: “It was before the age of microphones so it would really have been a wall of sound – and it was those things which really were crowd-pleasers”, as were penny subscription concerts, where people would pay 1d to attend a series of concerts.

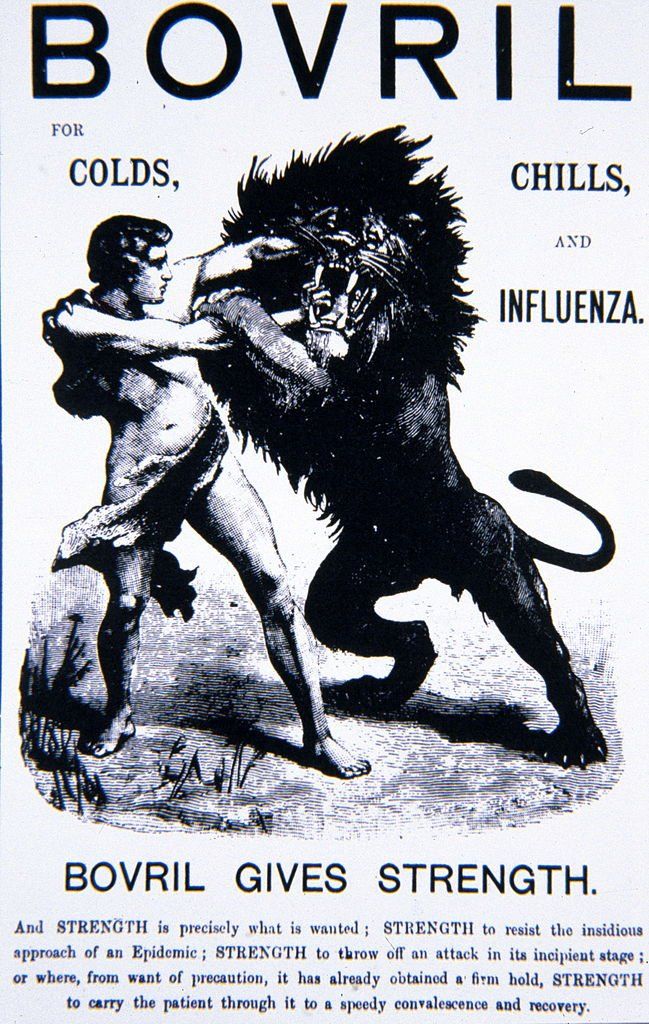

Other shows “just seem nuts now”, Ms Harper says. In March 1891, the hall was altered to resemble a city inspired by Lord Lytton’s science fiction story, Vril: The Power of The Coming Race (you can read it for free on Project Gutenburg) in which Earth is threatened by a winged master race called Vril-ya.

Thought to be the first ever sci-fi convention, exhibitors included a fortune-telling dog, various Vril-themed magic shows, and mannequins representing the Vril-ya.

image copyrightGetty Images

The novel was exceedingly popular with Victorians, who were quick to dress in costume for the event, with many donning wings. A more down-to-earth element was provided by possibly the longest-lasting legacy of the futuristic story: Bovril.

Worn-out attendees could pep themselves up with a cup of the hot beef extract, which had a display stall at the convention.

Its inventor named the drink by combining the words “bovine” and “Vril”. It was intended to symbolise the energy a mug of the salty blood-based liquid would give the drinker, and was probably an improvement on its original name of “Johnston’s Fluid Beef”.

image copyrightRoyal Albert Hall

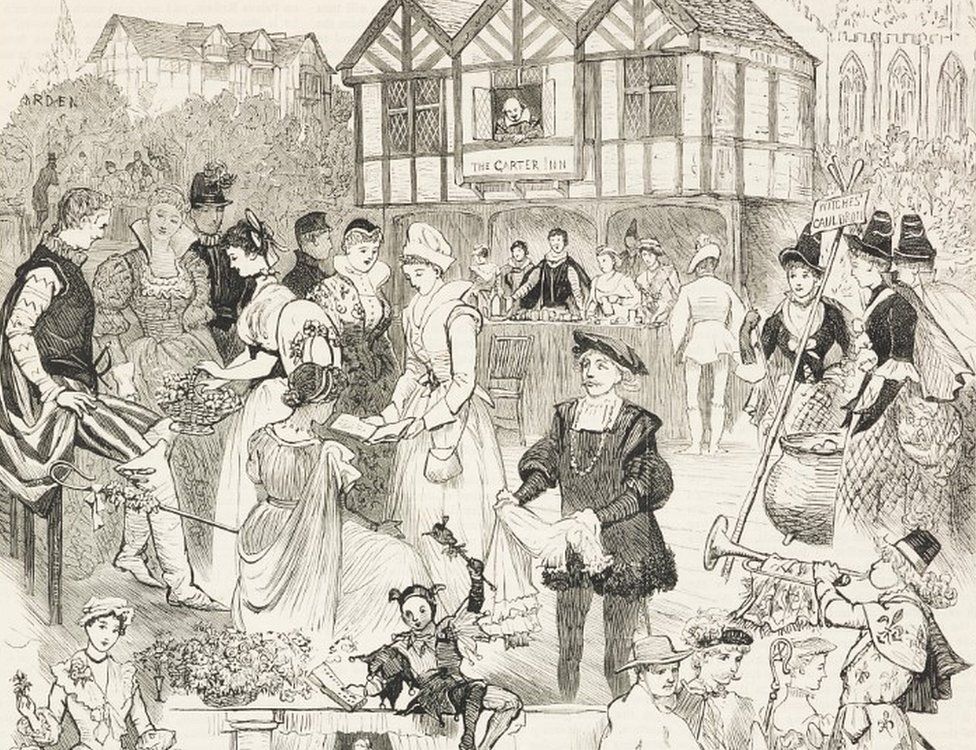

Never ones to do things by half, the Victorians also put on massive fetes, including one where they built a normal-sized church in the auditorium. The 1911 Shakespeare Memorial Ball saw the auditorium transformed with green lawns and real flowers, leading a rather star-struck newspaper reporter to write “never has the effect of a fancy dress ball, taken as a whole, been more wonderful or more complete”.

image copyrightGetty Images

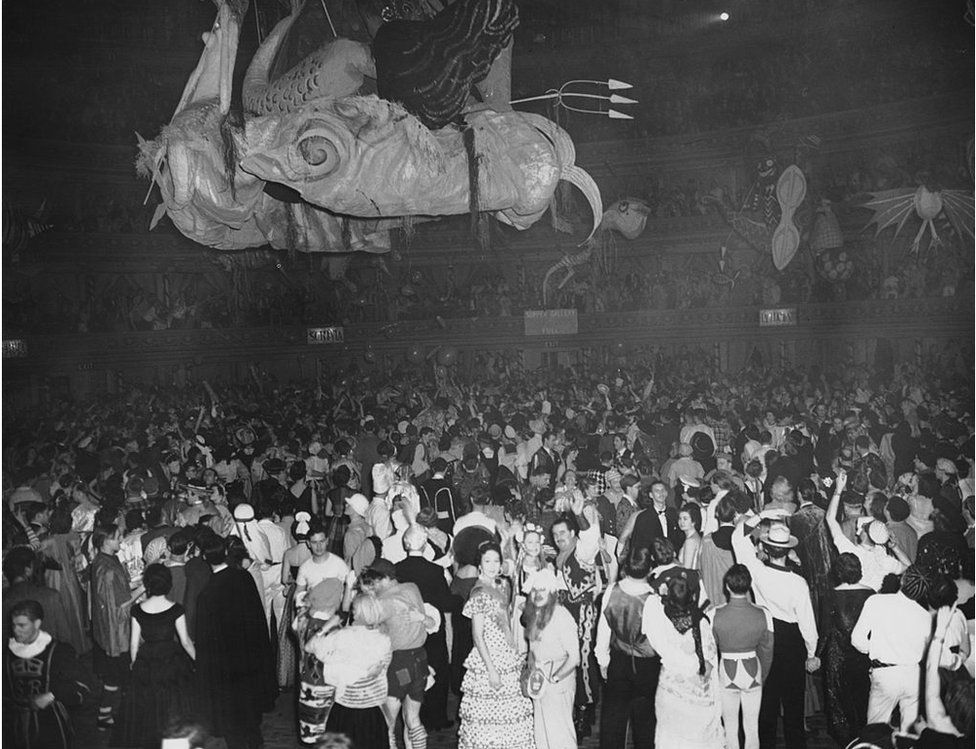

Costume Balls proved a good money-spinner – the first was held in 1883 by a London gentleman’s club The Savage Club, and Chelsea Arts Club Balls happened annually from 1910 until 1958.

Renowned for their exuberance and extravaganza, thousands of revellers dressed in historic or exotic outfits and cavorted on carnival floats driven around inside the huge auditorium.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty Images

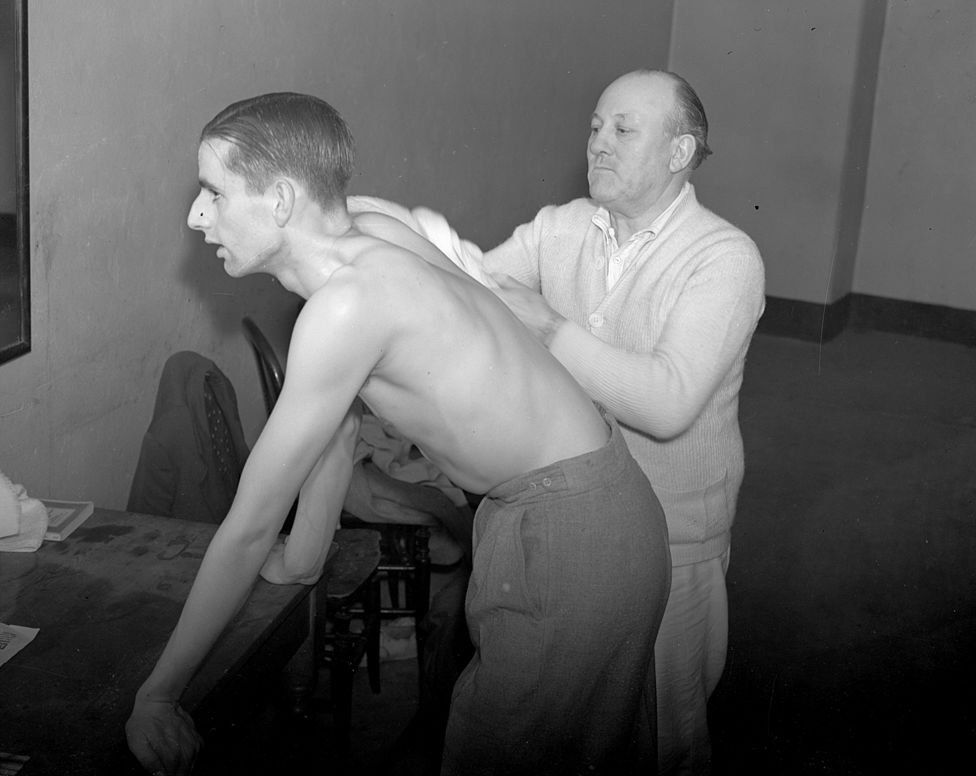

The great hall hosted a number of ground-breaking events – not just the first sci-fi convention.

What is thought to be the world’s debut bodybuilding contest, in 1901, saw 60 competitors trying to prove to a group of three judges who had the brawniest muscles.

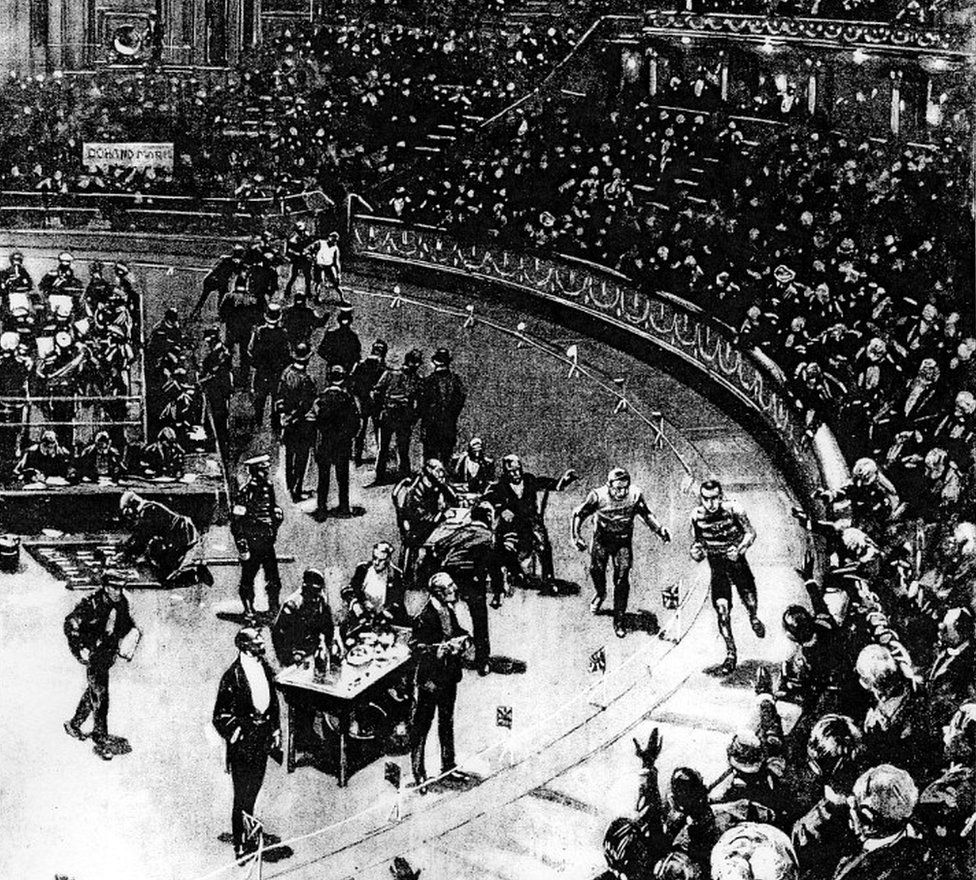

Britain’s first indoor marathon was held in December 1909, when two athletes – Italian Dorando Pietri and London-based C W Gardiner – attempted to run 524 laps of the auditorium.

Only Gardiner finished the race, completing the course in 2 hours and 37 minutes.

image copyrightRoyal Albert Hall

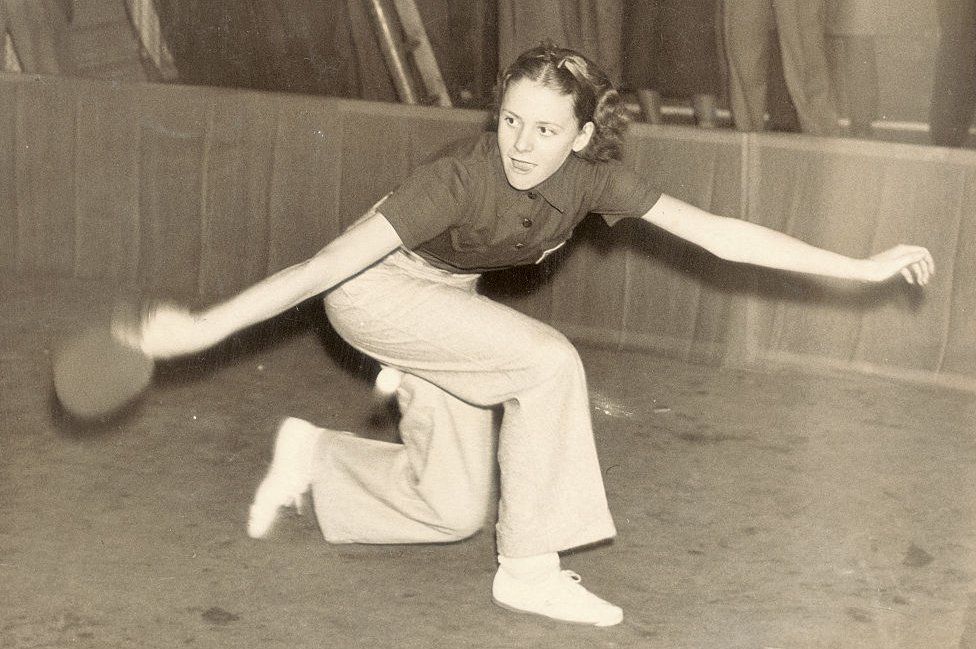

The first table tennis World Championship was played at the venue for five days in January 1938.

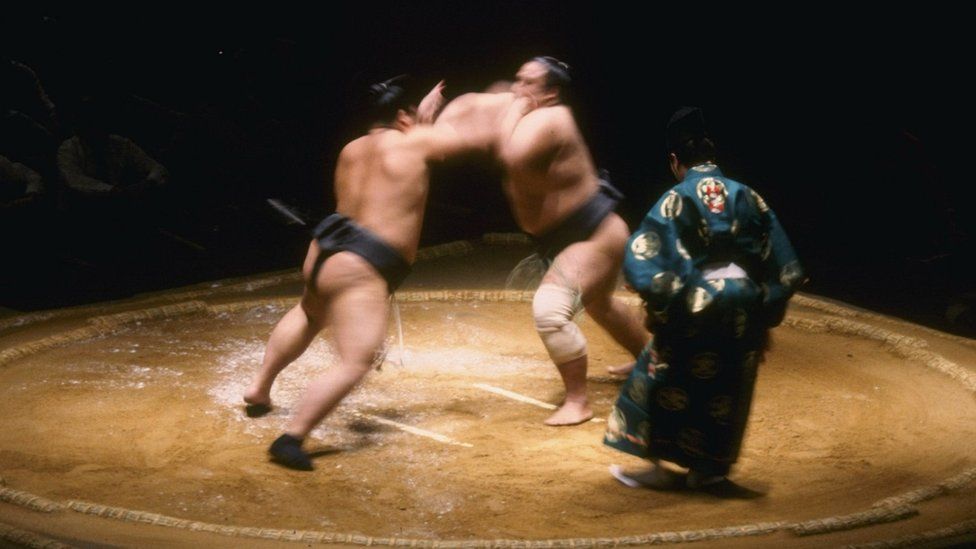

And the first sumo wrestling tournament held outside Japan in the sport’s 1,500-year history took place in the hall in October 1991, an event that necessitated the reinforcement of chairs, installation of extra-large showers and the weight-testing of toilets.

image copyrightGetty Images

As is to be expected, a venue that attracted such a range of events also pulled in the famous faces. Slightly oddly, the Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a judge for the rippling hunks in the bodybuilding competition.

He also sort-of turned up from beyond the grave. A séance was held days after his death in July 1930, in which a clairvoyant tried to contact him in front of an audience of 10,000 people and his widow, Jean.

Apparently her husband was reached, he passed on a message, and Lady Conan Doyle was “perfectly convinced” by the experience, which she found both “cheering and encouraging”.

image copyrightRoyal Albert Hall

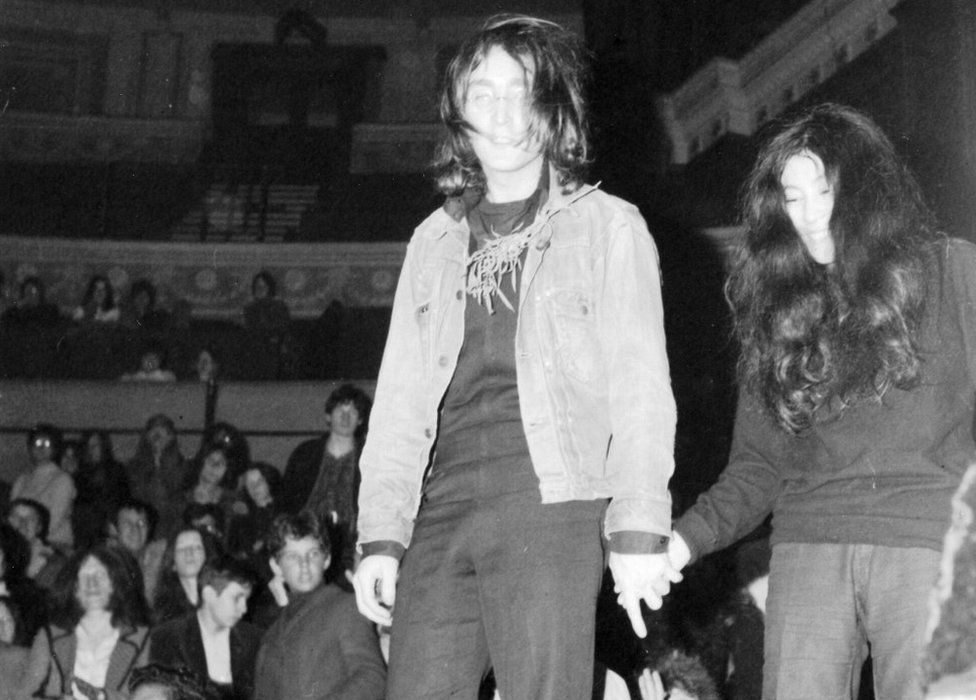

John Lennon appeared at the hall a few times – on one occasion triggering members of the audience to exhibit more than perhaps planned. In 1968 he and wife Yoko Ono put on a display called Alchemical Wedding, in which they sat in a large white bag while a man played a flute.

Some of the crowd showed their appreciation by getting naked in the auditorium.

image copyrightGetty Images

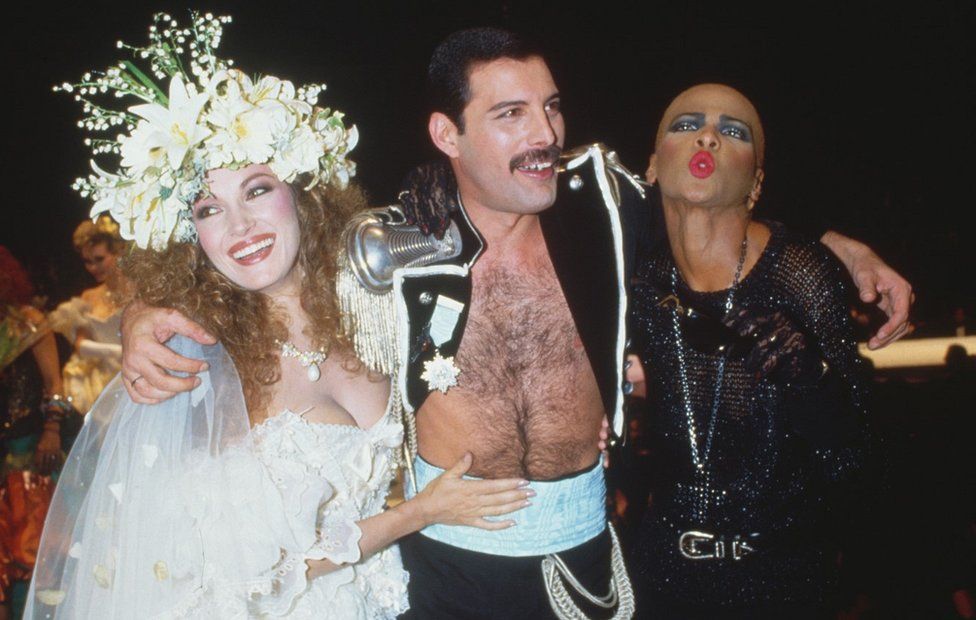

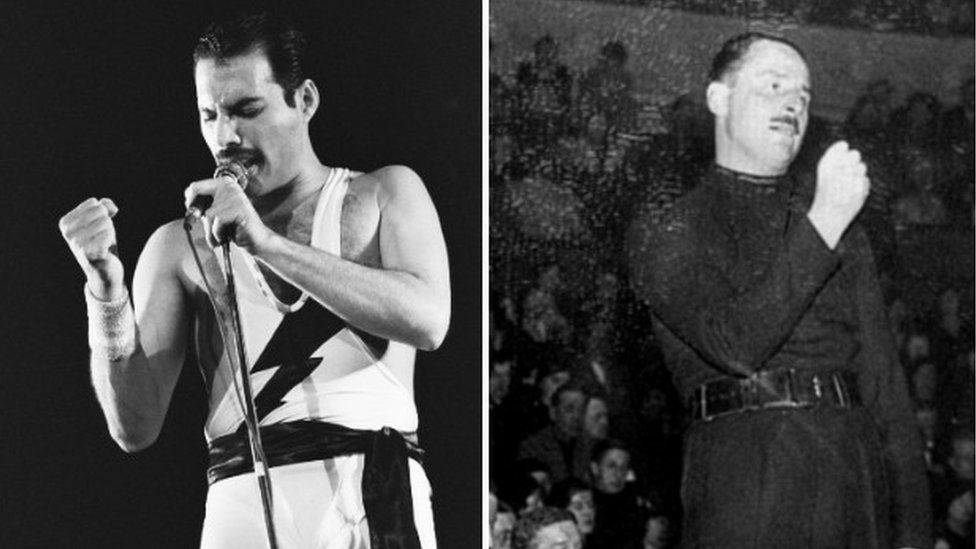

Fortunately clothes were on the menu in November 1985, which saw the arrival of Fashion Aid, a star-studded fashion-based off-shoot of Band Aid. It culminated with a fake runway wedding between Queen singer Freddie Mercury and actress Jane Seymour.

image copyrightGetty Images

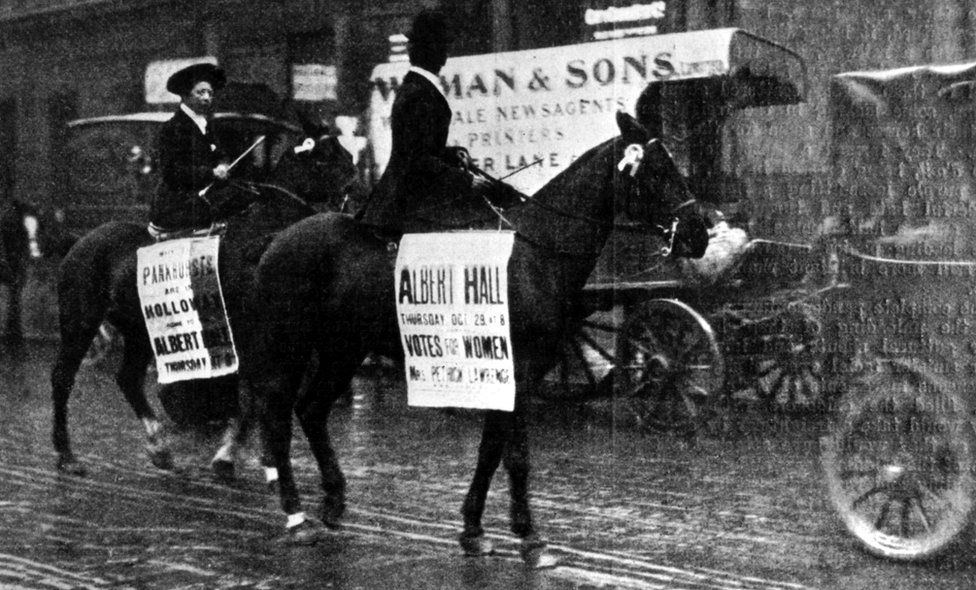

Not just the perfect place for the peculiar, the hall has seen its fair share of politics. Suffragists, suffragettes and anti-suffrage campaigners all rallied in the hall, which the suffragettes named their “Temple of Liberty”.

It was where Emmeline Pankhurst famously announced: “I incite this meeting to rebellion. Be militant each in your own way. I accept the responsibility for everything you do.”

“Lots of things have come forward from the hall to make wider social changes,” says Ms Harper.

“It was the largest venue where they could hire and it was where they raised the most funding.

“Women would literally take off their jewellery, their rings, their necklaces to put in the offering which was going round”.

image copyrightRoyal Albert Hall

The Suffragettes also have the dubious honour of becoming the first political group to be banned from the hall after some of the trustees became concerned that Pankhurst’s call for militancy could lead to trouble.

The auditorium was also the destination for several large meetings held by the British Union of Fascists during the 1930s. The Times newspaper reported that at one, in March 1935, the aisles were filled with Blackshirt squads who beat drums and sounded bugles.

Ms Harper says the current booking system is comparatively strict. “Back then, as long as they didn’t damage the hall, the trustees would take a booking from them because they needed revenue”.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty Images

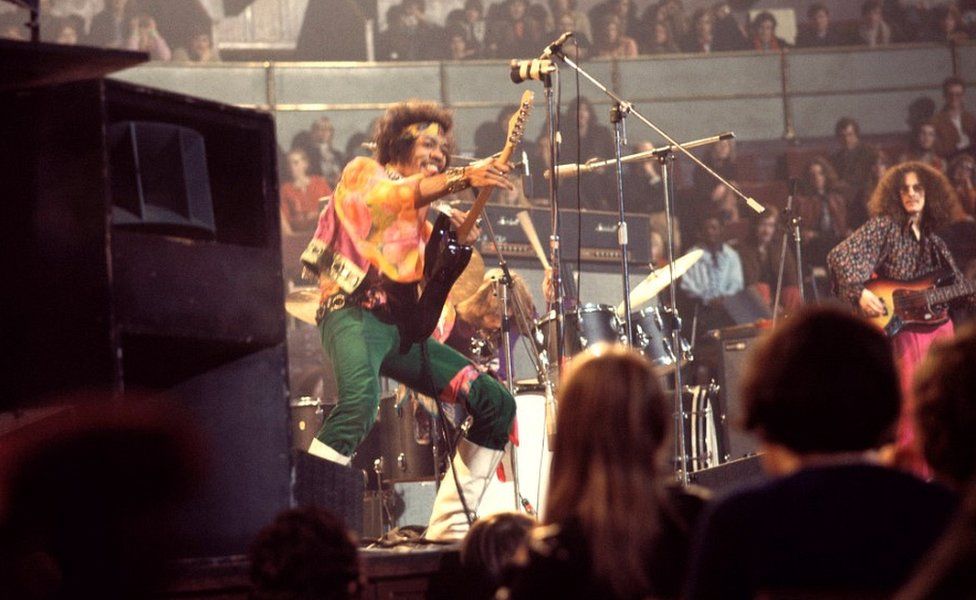

Pop and rock was once officially banned from the venue after performances by bands like Mott The Hoople and The Nice saw people ripping down curtains and breaking through the floor in the boxes.

Ms Harper says this meant the hall “wasn’t quite the really exciting place” it had been in the 1950s and 1960s.

image copyrightGetty Images

“You’d had these big counter-culture poetry gatherings, and massive rock gigs with Jimi Hendrix. And then in the 1970s you just had artists who were more like crooners”.

The ban was never officially lifted but as the management changed, the bands gradually returned.

In addition to indoor marathons and sumo wrestling, sport has played an important part at the hall, with tennis championships, boxing matches and table tennis championships all being held inside the hall.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty Images

The pandemic has delayed the hall’s 150-year celebration plans but chief executive Craig Hassall says he wants the programme to reflect the essence of what Prince Albert had planned all those years ago.

The Proms will return, along with their last night flag-waving. Both classical and pop concerts are scheduled, as are ballet performances, ballroom dancing competitions and gala evenings.

Or maybe Arthur Conan Doyle will make another return from beyond the veil – and this time he might be joined by some other Royal Albert Hall ghosts. Perhaps John Lennon, Freddie Mercury, Emmeline Pankhurst and Queen Victoria could share a nice cup of fortifying “fluid beef”.

All images subject to copyright

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.