Twenty years on from the start of the foot-and-mouth crisis, the Covid parallels appear stark.

image copyrightGetty Images

It was a rapidly-spreading virus, with stringent measures taken to contain its transmission. It delayed elections and had to a huge economic impact. Sound familiar?

On 19 February 2001 a case of foot-and-mouth disease was discovered at an abattoir in Essex.

By the time the outbreak was declared over it had spread across the British countryside and more than six million sheep, cattle and pigs had been slaughtered.

There had been major disruption nationally and, although the disease did not leap to humans, the overall cost to the UK economy was estimated at £8bn.

As with the current coronavirus crisis, there was criticism of the government for not shutting things down quickly enough, and in the early stages complaints of a shortage of equipment and resources.

Peter Frost-Pennington was a semi-retired vet who volunteered to help out in the unfolding crisis and was told to report to the operation centre in Carlisle.

He said: “I had my own boots, waterproofs and a thermometer, literally, there was nothing in stores. I had to bring my own bucket and brush; my own PPE effectively.

“It was only later [the government] opened the chequebook and also brought in the army.”

He described aspects of his work as “hugely upsetting”, having to slaughter animals when normally his job would be to save them.

“At one point I worked for 23 hours in a row culling infected animals”, he said.

“But I just took a deep breath and did my duty, like I’m sure people on the front line are doing now.”

One incident stood out; an infected farm where the young son had hand-reared a Highland calf which he was hoping would win a prize at a show the following week.

“He was trying to hide it in his bedroom,” Mr Frost-Pennington said.

“So I had to go in there and, as gently as possible, take it away from him.

“And then I had to kill it.”

image copyrightGetty Images

The crisis brought out the “best and worst of humanity”, the vet said.

“Sometimes it was a difficult job getting the message across to farmers that it was a very virulent disease and the infected animal was really dangerous.

“They might shout at me, and I can’t say I’d blame them.

“But there was also this time when I’d been on a farm for three days, slaughtering their entire herd of lovely pedigree dairy cows, and amongst all that they sent a bouquet of flowers to my wife because they knew I hadn’t been able to get home.

“I couldn’t believe their kindness, it was a wonderful thing.”

- The first case was detected at Cheale Meats abattoir in Little Warley on 19 February

- It affected cattle, sheep, pigs, and goats, causing fevers, blisters, and lameness

- Spread through the air and by direct contact with an infected animal, or contact with something contaminated by an animal

- Rarely affects humans, but they can spread the virus by carrying it on their clothes and bodies

- Probable source later traced to a pig-fattening farm on Heddon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland, where farmer Bobby Waugh was convicted of concealing that his herd had the virus and banned from keeping livestock for 15 years

- The crisis led to the cancellation of the Cheltenham Festival and delayed the local and general elections by one month

- Final case reported at Whygill Head Farm near Appleby, Cumbria, on 30 September

- More than six million animals were slaughtered, although some estimated it as far higher

- Cost the public sector ran to £3bn, while the private sector lost more than £5bn

Then, as now, there was social isolation and a toll on people’s mental health.

Bruce Jobson, who was then a Northumberland dairy farmer, said: “A lot of farmers have still not got over it.

“They refuse to talk about it because of the sheer horrendous conditions they endured.

“Animals were culled and left lying dead in the farmyards and the farmers just had to stay there because they couldn’t leave until everyone was gone and the animals had been taken away for disposal.

“It was horrific.”

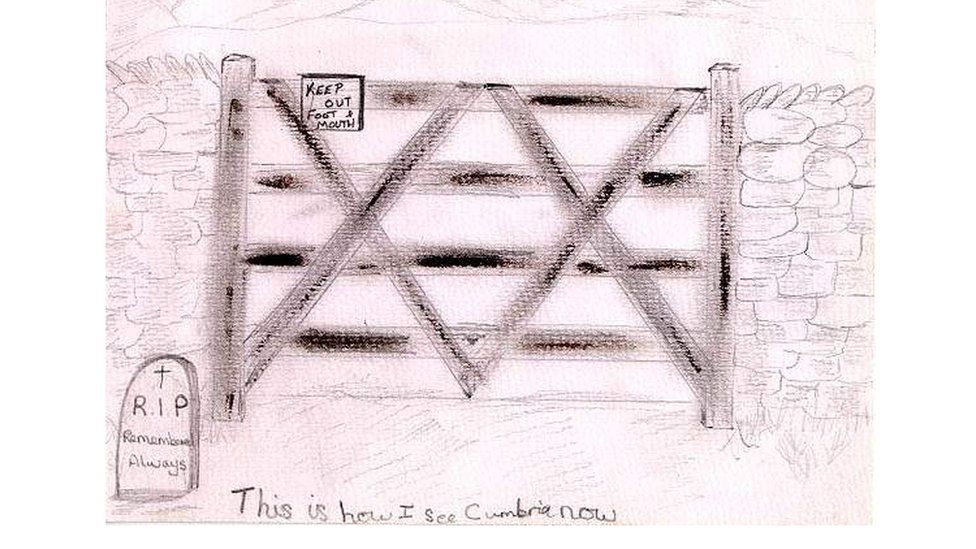

image copyrightVisit Cumbria

Kevin Holliday, who farms near Calderbridge in West Cumbria, said: “My children, then aged nine and 14, were unable to travel to school due to foot-and-mouth all around and we decided to send them away as full-time boarders.

“So we were on our own up here just [my wife] and I, and you know there’s a saying ‘a problem shared is a problem halved’? Well if you’ve got nobody to share it with because you’re all alone and isolated then it takes some stomaching.

“You’ve got to have some bottle to keep things going.”

His daughter Vicky added: “I remember seeing on the farm next to the school people with the suits on obviously taking the animals away to kill them.

“It will haunt me for the rest of my life.”

image copyrightGetty Images

Penrith dairy farmer Claire Bland had to contend with the slaughter of all the farm’s cattle.

She said: “The army came in and began the killing. We heard the first cattle bolt go, and then we just went inside.

“Afterwards, the countryside was just so quiet, there was no wildlife, there was nothing.

“It was a very dark time.”

Of the effects on mental health, she said: “I think I haven’t explored it completely. There’s a box in there with a lot of foot-and-mouth information that I haven’t gone through and I don’t think I ever will.”

image copyrightGetty Images

Farmers whose animals were culled were given payouts by the government, but those affected less directly were unable to claim compensation.

Julie Eakes, from Shipley in West Sussex, was a tenant farmer and having been given notice to quit the land had to get rid of her stock in one of the first farm sales after the outbreak.

She said: “In normal years you’d have a good farm sale which would have given us the ability to move on, but this year no-one wanted to buy anything.

“All that herd we’d built up over 18 years, rearing from calves, all the breeding ewes, we just got about 10% of what we would have.”

The family built up a farm business again, only to see the catering side which provided a “massive part of the income” collapse due to Covid restrictions.

They have been unable to access an insurance payout.

She said; “It’s devastating, brings back memories of foot-and-mouth and losing everything you’ve worked so hard for.”

The tourism industry was also hard-hit in 2001 as exclusion zones in affected areas meant swathes of the countryside was off limits and public footpaths were closed.

Cumbria was one of the worst affected areas, with the industry losing an estimated £260m.

Fast forward to the present day, where the impact of Covid has been described as the equivalent of “three winter seasons in a row”, and revenue is down by £2bn so far.

image copyrightPA Media

Jim Walker, vice chair of Cumbria Tourism, said: “It was a dreadful time for those involved – the farmers I talked to had a deeply personal investment in that way of life.

“It’s the same now in the tourism economy. A lot of businesses are very small and family-owned and people sink their personal savings into them.

“With foot-and-mouth it was ‘stop until it finished’, but there is a stop-start nature to [Covid] which presents more uncertainty, more of a unknown way forward.”

However, he remains hopeful for the future.

“After foot-and-mouth tourism did bounce back. The industry is very creative and innovative and we know there is massive pent-up demand, so there are opportunities as well as challenges.”

An inquiry into the foot-and-mouth outbreak criticised the government’s slowness to respond to the unfolding crisis and led to a major policy change in favour of vaccinating rather than slaughtering and burning animals.

Anthony Gibson, former SW regional director of the National Farmers Union, described it as “the biggest crisis in the Devon countryside, literally since the Civil War”, but is hopeful that it would not be repeated.

He said: “If we ever have an outbreak on the scale of the 2001 outbreak then vaccination would certainly play a key role.

“That would mean the countryside would not then have to be shut down in the way that is was in 2001, with all the damage to the wider economy and to tourism in particular.”

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.