A number of reports have raised concerns about the country’s only NHS gender clinic for young people.

image copyrightGoogle

In January, England’s only NHS gender clinic for children and young people was rated “inadequate” by the country’s health watchdog – the lowest rating, meaning it is performing badly.

The findings make for sobering reading with inspectors raising “significant concerns” about the way the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) works.

Nearly 5,000 children are waiting – sometimes for up to two years – for an appointment, and the management team has been disbanded following the inspection.

Now BBC News has had exclusive sight of an external report written in 2015 which recommended GIDS take drastic action.

It argued the service was “facing a crisis of capacity” to deal with an ever-increasing demand and strikingly it should “take the courageous and realistic action of capping the numbers of referrals immediately”.

With Care Quality Commission inspectors recently confirming many of the risks highlighted still remain, some have expressed concern about why neither GIDS, nor NHS England, which has ultimate responsibility for the service, have done more to help the children and young people it cares for.

By 2015 GIDS, which is part of the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, had been through a period of enormous change.

Six years earlier it had become a national service responsible to the central NHS and from that time demand rocketed – increasing 50% per year.

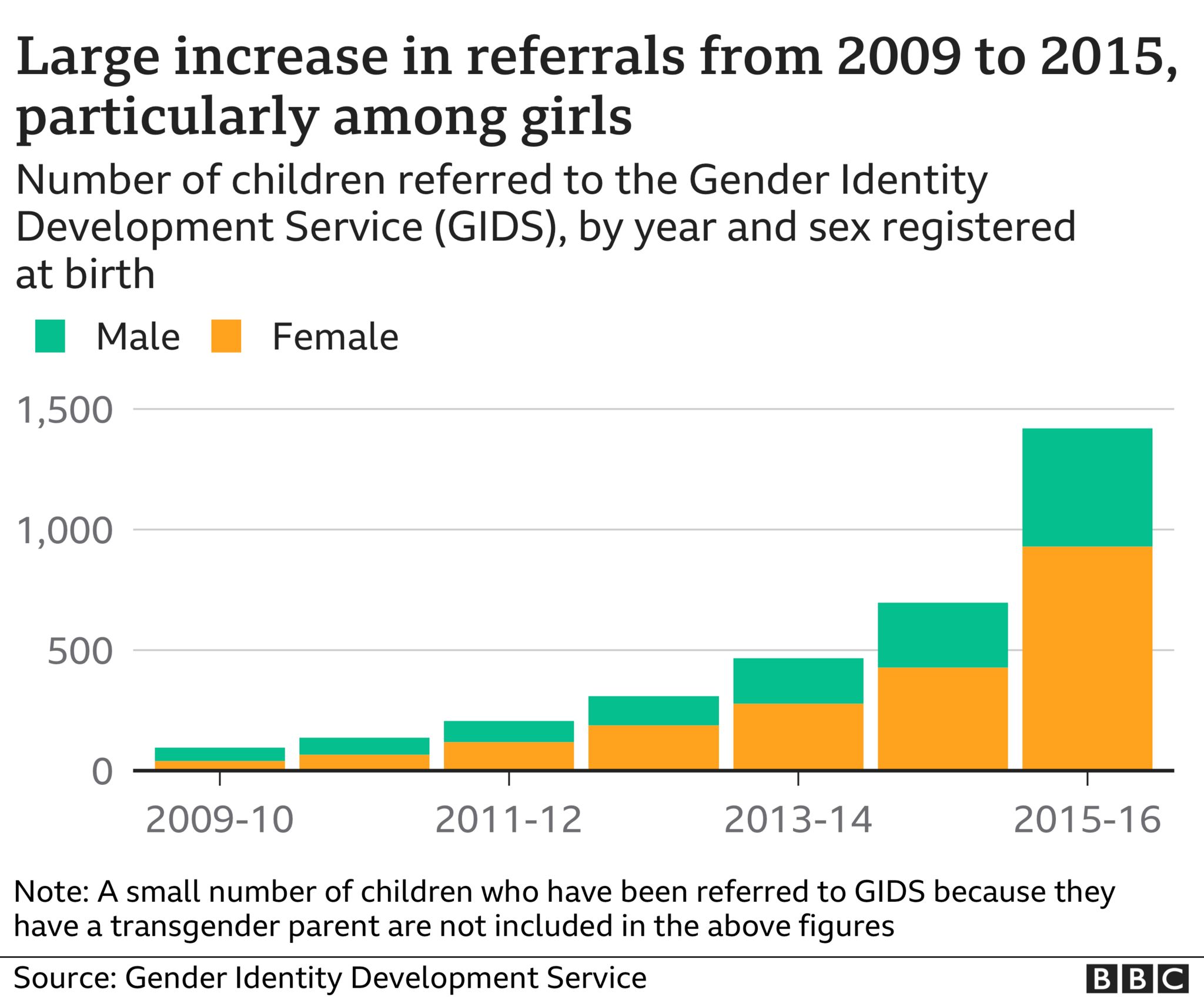

The number of children and young people referred to the service grew from 97 in 2009-10 to 697 in 2014-15.

A second base opened in Leeds in 2011 to help manage demand and ease travel for those living in the north of England.

But accompanying the increase in numbers was a shift in the type of patients being referred.

Since it opened its doors in 1989, around 75% of GIDS’ patients had been boys – natal males to use the language of the service at the time, now referred to as assigned male at birth.

In 2011, girls equalled boys in number for the first time. And by 2015 there had been a reversal in the sex ratio, with girls now outnumbering boys two to one.

What’s more, the nature of the cases appeared to have changed too. Young people often appeared to have complex mental health problems alongside their gender dysphoria – unease caused by a perceived mismatch between biological sex and gender identity.

Many were self-harming; others were struggling with depression, anxiety, bullying or eating disorders. Some suffered traumatic or abusive childhoods.

And finally, medical treatment had become more accessible.

In 2011, a study began to evaluate the impact of administering puberty blockers to younger children. By 2014, when the study had just finished recruiting its final participants, GIDS lowered the age at which young people could be referred for treatment with blockers from 16 to those in the early stages of puberty.

There was no lower age limit as such, but it meant in some instances that children of nine or 10 could now be eligible to be referred for this medical intervention.

By 2015 GIDS was struggling to cope.

Official Tavistock Trust board meeting minutes from 2015 support the idea of a service under immense pressure.

In February it’s noted GIDS is becoming more and more stretched, “with activity increasing faster than staffing”.

By June, the minutes are explicit: “The number of complex cases has increased” and it’s clear the environment is challenging.

Several GIDS staff are quoted, and while they enjoy their work one explains how the “demanding caseloads” can feel overwhelming and a “potential threat to the quality and level of work we are able to deliver”.

Another, with a caseload of around 90 young people, says this “can make it difficult to hold clients, their families and the professionals involved in mind”.

“We do not have the resources to offer therapy,” she adds.

Just a month later, the July 2015 minutes record that GIDS director Polly Carmichael acknowledged the service had reached a point where it “would have to say enough” and she was working on how to convey this to NHS England.

The Trust’s then medical director also conceded there was a sense of “escalating risk”, not just from work pressure but also in “the number of safeguarding and risk concerns being brought to him for advice”.

In September, GIDS missed its 18-week waiting time target for the first time.

Against this backdrop, an independent consultant was commissioned by GIDS managers to advise on how the service could adapt to meet growing demand.

One staff member, speaking on condition of anonymity, told the BBC: “We were under a lot of pressure.

“We just couldn’t meet the waiting time target. We hoped by having external consultants they could see what we were doing, because people in management were too close to it. We all were.”

Dr Femi Nzegwu, an international management consultant with over 20 years of experience, was chosen for the task.

Her report on ‘sustainable working’ paints a picture of staff struggling to provide the best care for distressed young people presenting to the service.

“I cannot continue indefinitely with such a high personal caseload with high levels of risk and complexity… without burning out,” one staff member is quoted as saying.

“Too busy to stop and reflect on cases and read through current literature which is very risky in this area.

Not all comments are quite so despairing, but there is broad consensus from staff that improvements could and should be made to the way GIDS operates.

It’s important to note that a minority of staff – 19 out of 55 – responded to the questionnaire which formed the basis of Dr Nzegwu’s report.

There’s no way of telling which roles they held – clinical or administrative. At the time GIDS listed its staff number as 34. But the questionnaire was also sent to those at the endocrine clinics that prescribe puberty blocking medication.

Dr Nzegwu found caseloads were “significant” and continuing to grow, “whilst resources are unlikely to grow to meet expanding needs”.

But perhaps most striking is her primary recommendation that GIDS should “take the courageous and realistic action of capping the number of referrals immediately.”

GIDS should pause. Even if for just a short period, while it reshapes the service.

It’s also recommended that GIDS “agree the criteria for referrals” and on “what the service can realistically deliver” with the resources it has.

Several staff have confirmed to the BBC most GIDS employees were never told of the recommendations.

The report’s findings were shared only during a meeting of the senior team. Serious consideration was given to the recommendation to stop accepting new referrals, the BBC understands. But it was not accepted.

One of those present told the BBC: “The report accurately reflected that we were in some kind of crisis.

“The workload was so overwhelming that we didn’t have time to stop, think and ask essential questions

“Had this report been acted on, and indeed even shared internally, GIDS and the Tavistock may have stopped themselves from going down a path which many, least to say some of its patients, may end up regretting,” they said.

It may seem like an extreme option to cap referrals, particularly when there are very distressed children at stake. But, it’s not unheard of. Several Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) have done this in the past.

Indeed, from the publicly available July 2015 board meeting documents, it appears this option had even been raised as a possibility by GIDS and the wider Tavistock Trust.

The minutes acknowledge referrals criteria might need to be toughened up, noting, “in some cases they might need to refuse a referral if they could not be sure of managing it safely”.

Some suggestions from Dr Nzegwu were acted upon.

Staff were placed into smaller, regional teams and a more obvious career structure was introduced over time.

The service began to assign a ‘complexity’ score to referrals – rating them low, medium or high. But three years later, in June 2018, GIDS director Polly Carmichael conceded, “referrals are received from anyone.”

The new scores did not impact on numbers. Referrals – which could come from GPs, schools, social workers, and even some charities and youth groups – exploded in 2015-16 at their fastest rate yet: more than doubling from the previous year to 1,419.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that having breached its 18-week waiting time target in September 2015, just seven months later waits for young people were approaching a year.

GIDS hasn’t met its target since.

The main change resulting from pressure on the service appears to have been a dramatic increase in the number of GIDS staff – predominantly at a junior level – a suggestion put forward, and funded, by NHS England.

Over the course of the following year the workforce doubled from around 40 to 80.

But this couldn’t solve the fundamental problems GIDS was facing.

The intention was for new junior staff to learn on the job by being paired with senior clinicians. It didn’t work out that way.

In GIDS’ own words: “The rapid growth in the service and associated increase in staff have presented challenges around ensuring adequate training and support for new staff.”

New staff found it “difficult to develop a caseload as quickly as … planned,” Polly Carmichael explained to the Tavistock Trust Board.

“As existing staff already have full caseloads it was difficult for new staff to find experienced co-workers to work with on new cases. The impact of this factor had not been fully appreciated when we recruited the staff,” she said.

But, was it wise to even attempt to staff a service helping a vulnerable patient group with junior staff, with limited clinical experience?

The NHS did not confirm if it had seen the 2015 report. An NHS spokesperson said: “The pressures on the Tavistock relating to rising demand for gender identity services are well known and the NHS has increased investment to respond to the demand for these services.”

Many of the risks highlighted in 2015 remained, and in most cases worsened, by the time the CQC’s inspectors visited GIDS in autumn 2020.

- Caseloads: In 2015 it’s claimed there was an “unspoken expectation” of 100 cases for full-time staff; the CQC says caseloads remain high, “stressful and difficult to manage”

- Patient assessments: Questions are asked about uniformity and minimum standards of report writing in 2015; the CQC describes assessments as “unstructured, inconsistent and poorly recorded”

- Risk: Staff raised concerns about the level of risk in the service in 2015; the CQC found GIDS did “not always manage risk well” both for patients in the service and those on the waiting list

There are now over 4,600 young people on that GIDS waiting list, with some waiting over two years for their first appointment. A far cry from the 18-weeks when Dr Nzegwu made her recommendations.

Dr David Bell, a highly respected psychiatrist at the Tavistock Trust, and one-time staff governor believes had the Tavistock responded in an “appropriate manner” in 2015 “further harm to children and young people might have been avoided”.

GIDS staff raised their concerns to him again in 2018 after they felt conversations with GIDS managers and other senior Tavistock Trust figures had made no impact.

He presented those concerns to the Trust’s board in August 2018, concluding that GIDS was “not fit for purpose” and “children’s needs are being met in a woeful inadequate manner”.

When he saw Dr Nzegwu’s 2015 report a year later, Dr Bell, who recently retired, said he was “very surprised to see a number of the concerns that were raised in my report, were either directly mentioned in this report or were related to them.

“There is of course a straight line from the concerns raised in this report and in my report to those in the report of the CQC.”

The Tavistock Trust’s medical director conducted a review of GIDS in 2019 in response to Dr Bell’s findings, and while the need for improvements was accepted, the Trust said, “it did not identify any immediate issues in relation to patient safety”.

When asked by BBC News, the Tavistock did not confirm whether anyone in the wider Trust – outside of GIDS – had seen the 2015 report, nor answer why its recommendations appeared to not have been acted upon and whether this could have impacted the current service.

In a statement, a spokesperson said: “GIDS is and has always been alive to issues relating to capacity in the face of rapidly rising referrals.”

“This has been the subject of ongoing discussions with NHS England,” they added.

“We are working closely with both the CQC and NHS England to work out how we can best manage demand for our service and those patients waiting to be seen. An action plan is in place.”

While advice from 2015 doesn’t appear to have been acted upon, it seems there was also limited support for GIDS patients from other services.

The surge in demand for GIDS’ expertise coincided with increased pressure on CAMHS.

“Some of the young people we see in the service experience difficulties which may or may not be related to gender dysphoria,” a Tavistock spokesperson told the BBC in October 2020.

For it to work at its best, GIDS relies on being able to work “closely with local CAMHS to support ongoing difficulties”.

“It is important to recognise not all co-occurring difficulties will be resolved by accessing specialist psychosocial exploration of gender identity and related issues,” they said.

There are also questions for NHS England. How was it that as reports questioning both GIDS’ model and, in later years, its ability to offer the best care possible to every single patient surfaced, it didn’t step in?

“An objective observer could see essential restructuring was needed to ensure a safe service for staff and patients as far back as 2015,” the GIDS staff member said.

Dr David Bell goes further.

“It is, to put it mildly, surprising that given the degree of mismanagement and serious neglect they [NHS England] have not intervened.”

The NHS announced an independent review into gender identity services for children and young people in September 2020, which GIDS supports.

That review, led by Dr Hilary Cass will “help ensure any child or young person, who may be dealing with a complexity of issues around their gender identity, gets access to the best possible support and expertise care,” an NHS spokesperson said.

Much now rests on the Cass review, which may yet take some time to complete.