The Budget – when is it, what does it do and what should we expect to hear from the chancellor?

image copyrightGetty Images

This year’s Budget will be very closely watched, because of the massive economic effects of Covid.

The choices Chancellor Rishi Sunak makes will shape the finances of the UK.

Each year, the chancellor of the exchequer – the government’s chief finance minister – makes a Budget statement to MPs in the House of Commons.

It outlines the state of the economy and the government’s plans for raising or lowering taxes. It also includes big decisions on what the government will spend money on.

The Budget also includes forecasts for how the UK economy could perform in future.

This year’s Budget speech will be delivered on Wednesday 3 March.

It usually starts at about 12:30 GMT and lasts around an hour.

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer gives his response straight afterwards. Then MPs debate the Budget and the Finance Bill, which puts the chancellor’s proposals into law.

The government says it will set out “the next phase of the plan to tackle the virus and protect jobs”.

The chancellor is under pressure to address two main issues:

- Whether the UK will begin paying off the huge debts built up during the pandemic

- How the government will support the people and businesses hit the hardest

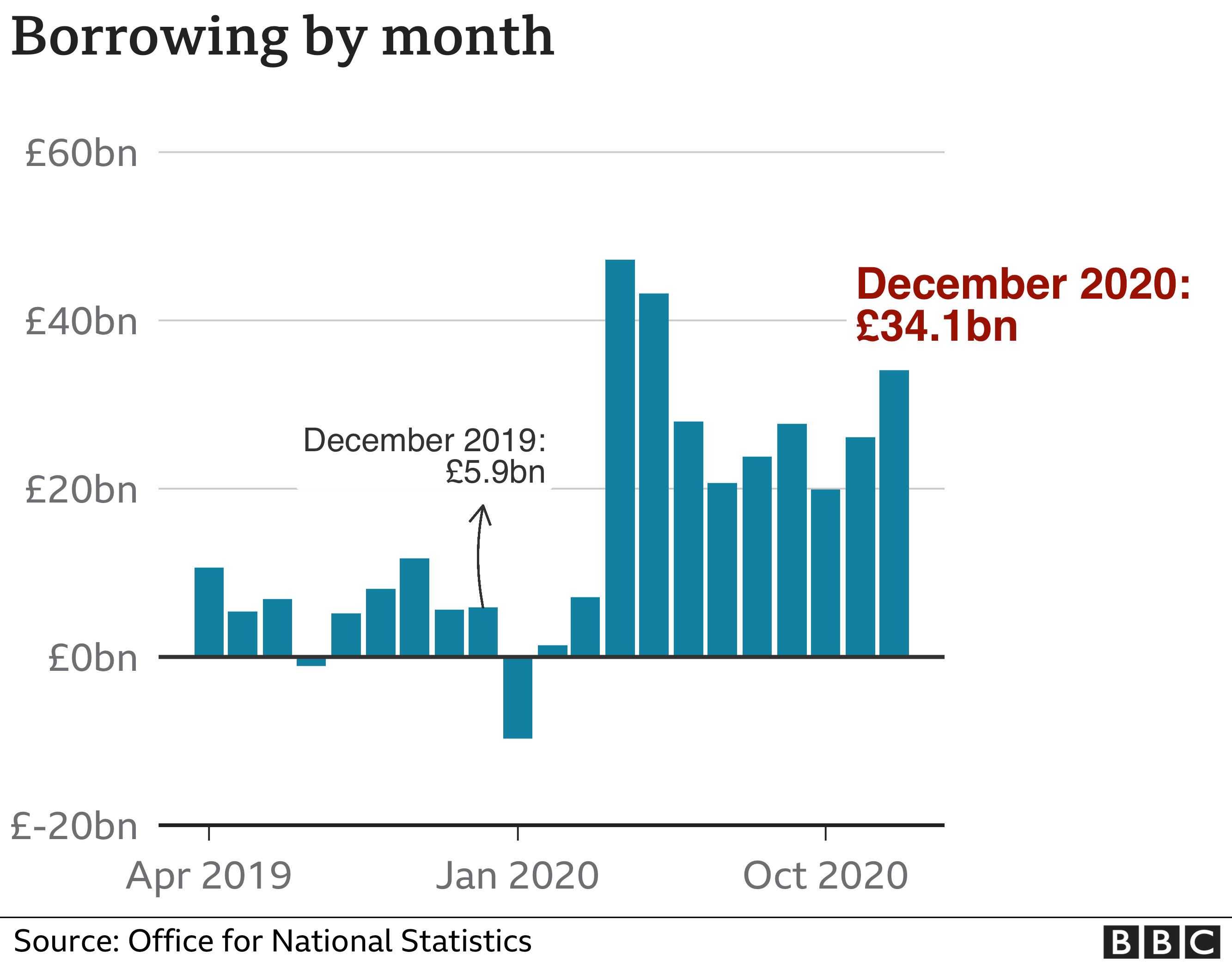

The latest figures are eye-watering.

Government borrowing for this financial year has reached £271bn. That’s £222bn more than a year ago.

This has pushed up the national debt to £2.13 trillion. That’s more than 99% of GDP – the value of goods and services produced by the UK. That has not happened since the early 1960s.

Million, billion trillion…

When the numbers get bigger and bigger, the words can start to sound the same.

But a billion is a thousand times bigger than a million. And a trillion is a thousand times bigger than a billion.

To put that into perspective, if a million seconds adds up to 11 and a half days, a billion seconds add up to 33 and a half years – and a trillion seconds? More than 33,000 years.

An awful lot, in other words. But in a modern economy we spend an awful lot.

If you take the total money spent on healthcare in the UK, it would, (according to the Office for National Statistics,) take less than five years to spend £1tn.

Alternatively £1tn could buy you more than four million houses at the average UK property price, or fund more than 500 NASA missions to Mars.

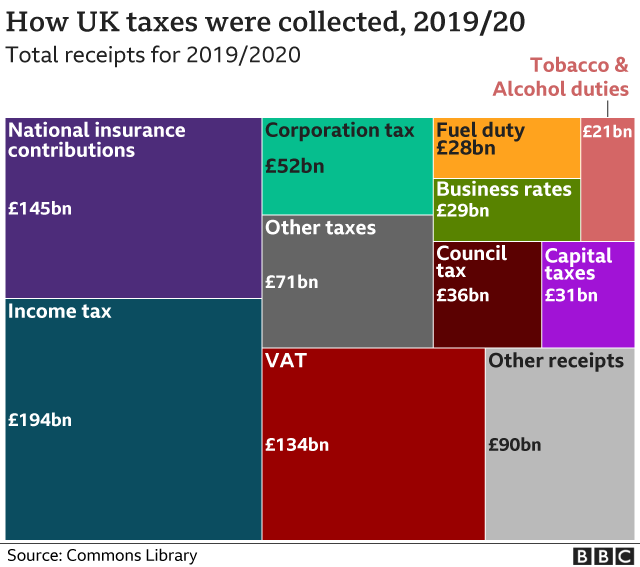

The government can raise money by increasing taxes. The three main ones are:

- Income tax on earnings, usually taken from your pay before you receive it

- National Insurance Contributions, another tax on earnings – paid by workers and employers – originally designed to finance benefits such as the state pension

- VAT – a tax added to the price of many goods and services

Before the 2019 election the Conservative Party said it would not increase these taxes.

But this was before the pandemic and the chancellor could argue circumstances have changed.

Some people say tax rises are needed and should be introduced quickly. Others say there is no need to act now because the cost of borrowing is cheap, and the economy is fragile.

Other measures could include a cut in government spending. Mr Sunak has already frozen pay for at least 1.3 million public sector workers.

The government has already confirmed it will extend the furlough scheme – where the government helps companies pay employees’ wages rather than lay them off – until September 2021.

In addition there will be further help for self-employed people who did not previously qualify for support during the pandemic.

The government is still under pressure to extend the £20 weekly increase to universal credit, which was introduced to support low-income families during the pandemic, but is due to end on 31 March.

There are also calls to keep the stamp duty holiday in England and Northern Ireland. This was designed to boost the housing market.

The chancellor sets the so-called “sin taxes” on cigarettes and booze.

Any change in these duties will come into effect almost immediately – although pubs may still be shut.

Some parts of the Budget, such as defence spending, affect the whole of the UK.

Others, such as education, only affect England. This is because Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland make their own decisions.

Scotland has income tax-raising powers, which means its rates differ from the rest of the UK. Its Budget is delivered on 28 January.

Wales controls some income tax too, but ministers have decided keep to the main UK levels.

In Northern Ireland, the Assembly has less control over taxes.