Ex-pupils caught up in the infected blood scandal decades ago will give evidence at an inquiry.

A public inquiry will this week hear from students and parents after more than 120 pupils at a school for disabled children were caught up in what has been called the worst treatment disaster in NHS history.

From 1974 to 1987, those children were offered treatment for haemophilia at Treloar’s College.

At least 72 died after being given a drug contaminated with HIV and viral hepatitis.

“We’ve lost so many friends from Treloar’s and it’s absolutely heartbreaking,” said Richard Warwick, a pupil at the Hampshire school in the late 1970s who was later diagnosed with HIV.

Former headmaster, Alec Macpherson, is also due to answer questions. “It caused those boys a lot of anxiety and a lot of upset,” he told the BBC ahead of the hearing.

“It put a rage inside them – why me, why has this happened to me, why have I got this dreadful disease?”

Lord Mayor’s Treloar’s College was a boarding school for physically disabled children with a specialist NHS haemophilia centre on site, run by a dedicated medical team.

By the mid 1970s, a new treatment for haemophilia, known as factor VIII/IX, became available for the first time.

It meant those with a serious form of the blood disorder could live a normal life without the risk of a bleed.

The NHS was not self-sufficient in the blood plasma used to make the drug so it was imported from overseas, most notably the US.

Batches were widely contaminated with hepatitis A, B, C and later HIV, infecting thousands of haemophiliacs across the UK.

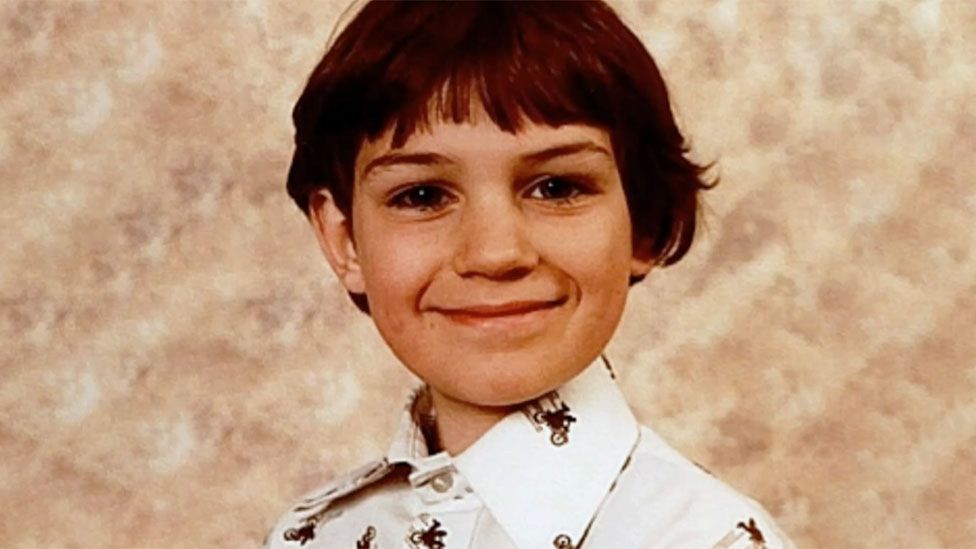

Ade Goodyear joined Treloar’s in 1980 at the age of 10. He described life as “wonderful” with supportive teachers, nurses and good friends.

Like dozens of other boys at the school, he was given factor VIII to help control his bleeding.

image copyrightAde Goodyear

“With one of my very first shots, I got hepatitis and was placed in isolation for two weeks,” he said.

In 1985 he was taken into a small office with a group of boys to be told he had tested positive for HIV – then a newly discovered virus with no known treatment and a short life expectancy.

“The doctor was upset and pointed at us and said, you have it, and you haven’t. And I was back in science by 1.50pm. I didn’t even get the afternoon off,” he said.

“A friend of mine picked up a pot plant and threw it against the wall of the haemophilia centre. It was a beautiful summer’s day and I remember thinking, how many more sunrises like this am I going to see?”

Ade’s two older brothers died after treatment with factor VIII – Jason from Aids in 1997 and Gary from health problems linked to hepatitis C in 2015.

For pupils like Ade and Richard it meant living with the stigma of what was then a little-known disease.

Students were followed by newspaper reporters outside the school gates and shouted questions about their HIV status.

Just 32 of the 122 haemophiliacs who attended the school from 1974 to 1987 are still alive today. Most died after contracting HIV or viral hepatitis.

It’s hoped the public inquiry will be able to answer questions about what happened at Treloar’s and the NHS haemophiliac centre run from the site.

Families want to know why they were not told about the potential risks of Factor VIII earlier and why it took many years until the drug was heat treated to kill viruses and other contaminants.

“What happened at the school comes back to haunt us every day,” said Stephen Nicholls, a former pupil who was infected with hepatitis C after his treatment.

“We will never forget the Treloar’s story and those memories of what happened here.”

It is a rare genetic condition in which the blood does not clot properly. It mostly affects men.

People with the condition produce lower amounts of the essential blood-clotting protein known as factor VIII and IX.

Former students will give evidence this week, some anonymously, along with the parents of children who lost their lives.

The haemophilia centre on the site was run by NHS doctors and nurses and not staff directly employed by the school, which still cares for physically disabled children today.

“Although no-one has at any point suggested that Treloar’s was at fault, it is a tragic part of our past,” the school said in a statement.

“It was, and still is, a very difficult time for our affected alumni, their families and staff who were here at the point.”

Have you been affected by the issues raised in this story? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

If you are reading this page and can’t see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.