Apple and Google’s rules state that no location data from app users can be shared.

image copyrightPA Media

An update to England and Wales’s contact tracing app has been blocked for breaking the terms of an agreement made with Apple and Google.

The plan had been to ask users to upload logs of venue check-ins – carried out via poster barcode scans – if they tested positive for the virus. This could be used to warn others.

The update had been timed to coincide with the relaxation of lockdown rules.

But the two firms had explicitly banned such a function from the start.

Under the terms that all health authorities signed up to in order to use Apple and Google’s privacy-centric contact-tracing tech, they had to agree not to collect any location data via the software.

As a result, Apple and Google refused to make the update available for download from their app stores last week, and have instead kept the old version live.

When questioned, the Department of Health declined to discuss how this misstep had occurred.

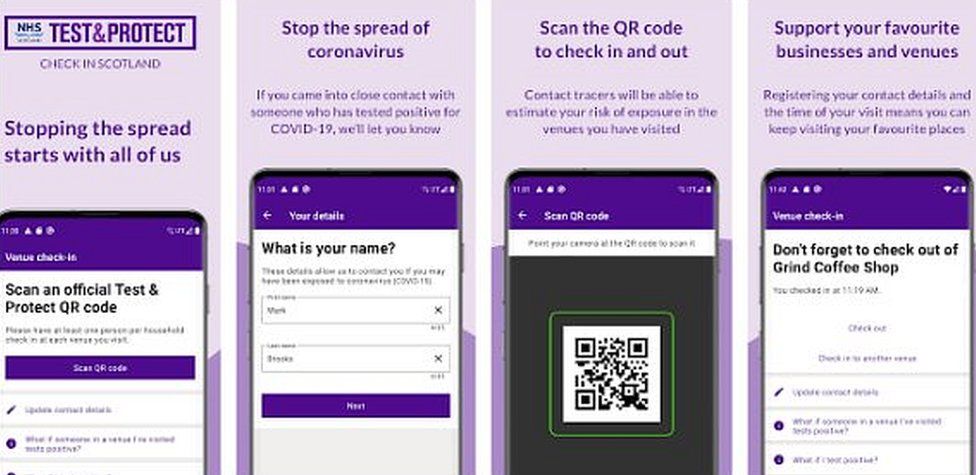

Scotland has avoided this pitfall because it released a separate product – Check In Scotland – to share venue histories, rather than trying to build the functionality into its Protect Scotland contact-tracing app.

image copyrightNHS Scotland

NHS Covid-19’s users have long been able to scan a QR code when entering a shop, restaurant or other venue to log within the app the fact that they had visited.

But this data has never been accessible to others.

Instead, it has only come into use if local authorities have identified a location as being a virus hotspot by other means, and flagged the fact to a central database.

Since each phone regularly checks the database for a match, it can alert the owner if they need to take action as a consequence, without sharing the information with others.

However, this facility has rarely been used, in part because prior to the most recent lockdown, many local authorities were confused about what they were supposed to do.

Before shops reopened in England and Wales on Monday, along with outdoor hospitality venues in England, the intention had been to automate the process.

This would have involved users who had tested positive being asked if they were willing to upload their logs.

Depending on the thresholds set – for example, how many infected users registered having visited the same place on the same day – other app users would then have been told to either monitor their symptoms or immediately get a test, whether they felt ill or not.

The Department of Health had described this as being a “privacy-protecting” approach.

But despite being opt-in, it was still a clear breach of the terms that health chiefs had agreed to when they switched to adopting Apple and Google’s contact tracing API (application programming interface) in June 2020. This was after their original effort was found to miss too many potential cases of contagion.

The tech firms’ Exposure Notifications System FAQ states that apps involved must “not share location data from the user’s device with the public health authority, Apple, or Google”.

And a separate document covering the terms and conditions in more detail says that “a contact tracing app may not use location-based APIs… and may not collect any device information to identify the precise location of users”.

Had Apple and Google made an exception for England and Wales in this case, it could have set a precedent for other countries to have sought changes of their own.

The team behind the app was told not to disclose why the update had failed to be released on schedule.

A spokeswoman for the Department of Health told the BBC: “The deployment of the functionality of the NHS Covid-19 app to enable users to upload their venue history has been delayed.

“This does not impact the functionality of the app and we remain in discussions with our partners to provide beneficial updates to the app which protect the public.”

A spokeswoman for the Welsh government said it had nothing to add.

Just a week ago, the Department of Health seemed to think this update to the app would go through without problems.

It’s hard to understand why. After all, the rules for using the Apple-Google Exposure Notification System were clear – collecting any location data was a no-no.

The app team knew that when they switched to it last summer, having discovered that going it alone with their own system was just not practical.

But they may have assumed that, because the sharing of locations by users was optional, the tech giants might show some flexibility.

Instead, Apple and Google have insisted that rules are rules.

What this underlines is that governments around the world have been forced to frame part of their response to the global pandemic according to rules set down by giant unelected corporations.

At a time when the power of the tech giants is under the microscope as never before, that will leave many people feeling uncomfortable.