Brigadier John Clark says the British army will become “leaner”, ahead of the defence review.

image copyrightAFP

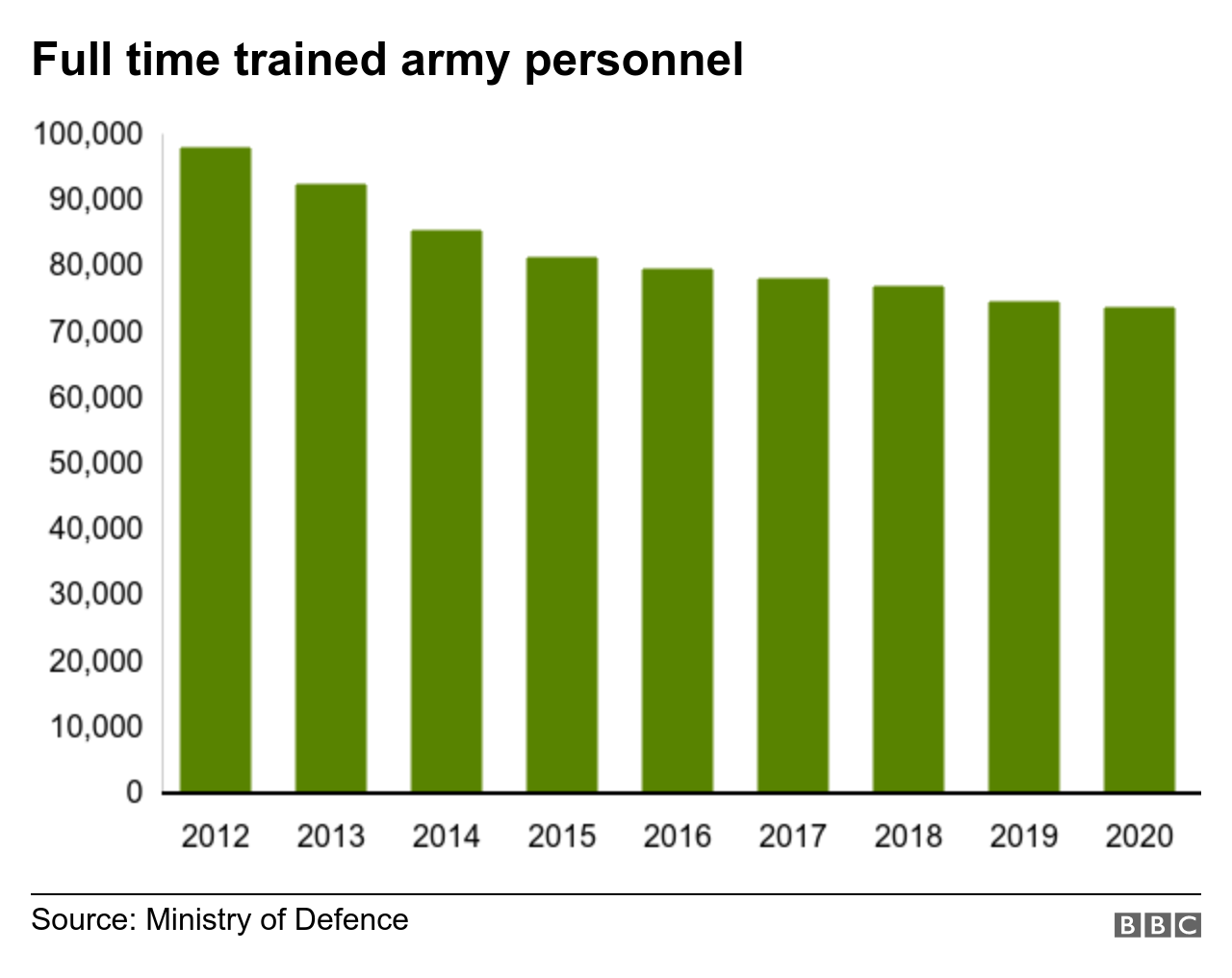

The British army is already the smallest it’s been in 400 years. And it’s about to get even smaller.

A cut in the number of troops is expected in a defence review, due to be published next month.

Options include losing up to 10,000 soldiers from the regular Army’s notional strength of 82,000 in order to help fund its modernisation.

Ministers have made clear there will still have to be painful decisions for the armed forces, despite the extra £16.5bn given to the Ministry of Defence over the next four years.

A senior Army officer has told the BBC that technology will allow the Army to become “leaner and more agile”.

But it comes amid warnings that the Army is already too small, and that more cuts will worry allies and limit its ability to fight.

Over the past year the Army has been preparing for a radical transformation.

It wants to embrace new technologies – from drones and robots to artificial intelligence.

Brig John Clark, the head of Army strategy, insists no decision on troop numbers has yet been made.

But he says by harnessing technology “you’re able to achieve the same effect with fewer people”.

However, Jack Watling, of London’s Royal United Services Institute warns of “the excitement of new capabilities coming at the expense of traditional hard military power”.

Remember, the majority of soldiers in a modern army are there to support and sustain a fighting force.

The tip of the spear, the combat element, is often about a third of an army’s total strength.

image copyrightGetty Images

The rumours in Whitehall suggest the Army will be losing several infantry battalions, part of the fighting force.

Mr Watling says an army of just 72,000 should still be able to take and hold “a small town”, bearing in mind the British army struggled to secure the Iraqi city of Basra, when it was 100,000 strong.

It might appear to be a contradiction, but the Army believes even if it’s smaller, it can still have a bigger presence around the world.

It’s embraced the government’s mantra of “global Britain”.

For the Army it’ll mean operating from a number of “global hubs” in parts of the world where it already has a presence – such as Kenya, Oman and Brunei.

Brig Clark says: “We see those as launchpads through which we can routinely send more of the British army out to train, develop and demonstrate.”

He says by being forward-deployed the Army will be able to respond and manage threats “more rapidly and decisively”.

He describes it as prevention rather than cure.

It signals a shift in the way the Army wants to operate.

Brig Clark talks of “smaller teams that can go out there and compete beneath the threshold of conflict” – the so-called “grey zone” where militaries operate discreetly in the blurred lines between war and peace.

Ben Barry, of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), said: “I see a clear aspiration to do more with the Army further away, but forces cannot be everywhere at once.”

There are certainly questions as to whether a smaller army, spread around the world, will be able to meet its existing commitments to Nato (North Atlantic Treaty Organization).

In theory, the UK can deploy a war fighting division to defend Europe.

Mr Watling of Rusi says among the components of a division would be around 200 main battle tanks.

The British army is likely to have half that number.

Mr Barry, of the IISS, says allies in eastern Europe are left wondering whether the British army of the future will be sending “armour and infantry or aggressive algorithms” to help defend them.

The Army’s plans do include updating increasingly obsolete armoured vehicles and the addition of more potent long-range artillery systems.

Brig Clark insists the Army will still be able to field a warfighting division.

But the Army’s definition of a division appears to be changing.

The UK already has one of the smallest armies of any major European nation.

And that worries its closest military ally, the United States.

US General Mark Milley’s plea to the British army at a London conference just a few years ago was that “you don’t get any smaller”.

Kim Darroch, the former British ambassador to Washington, recently said the message from the Pentagon was “…do not go down any further and expect to retain your current credibility”.

The truth is that the British Army’s credibility had already been damaged in the eyes of the US.

America had to come to the rescue of the British army in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

Mr Barry and Mr Watling also question whether an army of 72,000 could do another Helmand – a long, enduring campaign.

Brig Clark insists it could.

But the British army has a recent history of biting off more than it can chew.